Tanzania is almost the perfect East Africa destination. With lakes and mountains, endless backroads and small towns, a fascinating and exotic coastline, and one of Africa’s most proud and distinctive people, there is a lot more on offer than safaris, Mount Kilimanjaro or the island of Zanzibar.

Tanzania – Population: 68M | Capital: Dodoma | Language: Swahili | Currency: Shilling

A man pedals lazily through the gentle streets of Mikindani.

(This is the third blog post in a series following my recent trip to Africa. You can read the first two posts, “Zimbabwe”, and “Malawi”, here).

Officially “The United Republic of Tanzania”, Tanzania sits in the Great Lakes region of East Africa. The country has a long Indian Ocean coastline dotted with islands and large ports, as well as claims to large stretches of land alongside Lake Nyasa (also called Lake Malawi—in Malawi), Lake Tanganyika, and Lake Victoria. With a population over 65 million, Tanzania is the most populous country located entirely south of the equator (who knew?). Like other neighboring countries, Tanzania is home to many ethnic groups, tribes, and regional languages, but despite that there’s a definite feeling of “One-ness” that you don’t find in other African countries, due mostly to the strong Swahili culture and language that defines it.

Bukoba town on Lake Victoria, taken from a bluff above farmland to the south. It was my last full day in Tanzania; I left the next morning for Uganda.

Outside of Africa, Tanzania is known primarily as a tourist destination for well-organized—and expensive—game safaris. Around 38% of the country’s land mass is set aside in protected conservation areas where you can find “the big five”: lions, elephants, rhino, leopards, and buffalo. Ngorongoro and Serengeti are the game parks most people have heard of, but there are 14 other national parks, including Gombe, famous for Jane Goodall’s study of chimpanzee behavior (still ongoing, by the way). The semi-autonomous island of Zanzibar is also popular, for its beaches and cool Afro-Arab-Swahili vibe. Adrenaline travelers can climb Mount Kilimanjaro, Africa’s highest mountain at 4,877 meters (16,000 feet).

Some of the weird and wonderful rock formations on Lake Victoria at the port city of Mwanza. Also known to residents as “Rock City”, Mwanza is Tanzania’s 2nd largest city, with close to 4M residents.

The economy of Tanzania is defined as “lower-middle income” and is focused on manufacturing, agriculture, and tourism. Tanzania doesn’t seem lower-middle-income for the most part, to me anyway, as many of the smaller towns and villages are still largely undeveloped and basic. But it’s noticeably “less poor” than neighboring Malawi or Uganda, which you can really notice in the sturdier shops and office buildings, better quality streets and highways, and greater variety of non-essential items for sale in the markets.

I was afraid to ask…

All told, tourism accounts for nearly $3 billion of Tanzania’s economy—nearly 10%—and is the country’s third-largest source of employment. But outside of the national parks, Mount Kilimanjaro and Zanzibar, foreign visitors are few and far between—nearly completely absent, really. You likely won’t be surprised to learn I didn’t visit the national parks, Mount Kilimanjaro, or Zanzibar, and instead headed for the smaller towns and remote districts where I loved walking in the surrounding countryside, drinking in the pubs, chatting to the locals and wandering through the towns.

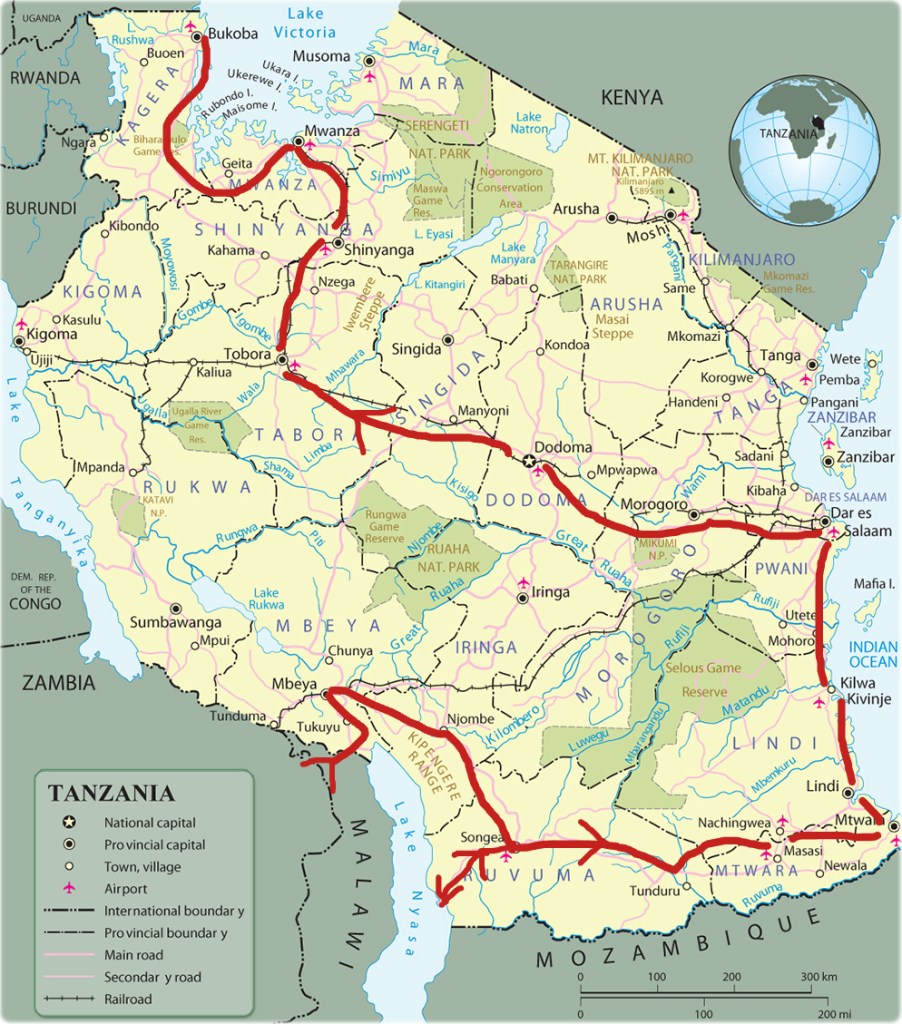

My Route

My route through Tanzania: I entered from Malawi, then traveled east to the Indian Ocean coast, then turned north to Dar es Salaam where I cut left and crossed the hot, flat central plains to Lake Victoria.

One of my main targets was route A19 in the south, which runs from Mbamba Bay on the shores of Lake Nyasa, to the Indian Ocean port of Mtwara. I first heard about the A19 in 1993 from my travel buddies Rob and Fiona when we met in Ethiopia. They had driven the stretch in their beat-up Land Rover, and regaled me with tales of rough adventure across an uneven dirt and gravel back-of-beyond route through a nearly undiscovered section of the country (you can read about it in my book, Resting With Old Man). The A19 is busier now, and the road is paved in its entirety, but it’s still most definitely back-of-beyond, and is fascinating. With the exception of only a few sections, I hitchhiked the entire route, mainly in the cabs of large trucks hauling coal to the Indian Ocean port at Mtwara.

I spent 33 days in Tanzania in July and August of 2024. This was my third visit to Tanzania, but this time I covered mostly all new ground.

Sights and sounds in Njombe Central Market. The large markets in Tanzania were a little better stocked than in Zimbabwe or Malawi.

Getting In & Out

Most nationalities need a visa to enter Tanzania for tourism, but luckily they’re available on arrival for US$50. I crossed at the Songwe crossing in the far north of Malawi. Malawi and Tanzania share an integrated “one-stop border post” where immigration officials from both countries sit under the same roof, rather than in separate buildings. In theory this is supposed to simplify and speed up formalities, but I’ve always found the one-stop borders equally as chaotic and unorganized. The entire process took about 45 minutes. I changed my remaining Malawi kwacha into Tanzanian shillings with one of the ubiquitous money changers loitering just far enough out of eyeshot of the police, then bought a local SIM card for my phone in Tukuyu, the first town after the crossing. I eventually left Tanzania for Uganda at the Mutukula border crossing near Lake Victoria in the far north.

A man zips by on his motorcycle in Mikindani, my first stop at the Indian Ocean on the Swahili Coast.

Swahili

Tanzania is at the same time both similar to its neighbors, and different. Similar in that the towns look more or less the same, with the familiar straight streets lined with concrete and wooden shops, sprawling markets, informal eateries and rickety houses. The villages and hamlets are the same, largely rural and undeveloped. The countryside is just as beautiful and bucolic as in Malawi and Uganda and Kenya, with fresh green fields, tidy subsistence farms and cozy little houses and gardens. What makes Tanzania different is the large stretch of the Indian Ocean shore, known as “the Swahili Coast”, and the culture and language the region spawned.

The Swahili people were traders and merchants who lived on or near the Indian Ocean coast of what is today Kenya, Tanzania, and Mozambique. From early times, most of the African seaboard from the Red Sea to an area south of what is today Mozambique was under the dominion of Arab traders, who dealt in ivory, spices, and slaves. Mombasa, Zanzibar, Pemba, Kilwa Masoko, Mtwara were all major centers of Arab wealth and trade. The African inhabitants easily absorbed language and cultural influences from the Arabs, mixing it with their own indigenous societies.

A proud mother in Mikindani. The Swahili people in the southern and coastal towns of Tanzania show a fascinating mix of African and Arab influences.

For much of their early history, the label of “Swahili” people and culture was reserved for people who lived near the coast, and whose language reflected a mix of African and Arabic cultures. More recently, however, through a process of “Swahilization”, Swahili has come to refer to any person of African descent who speaks Swahili as a first language, is Muslim, and lives in a town in Tanzania and coastal Kenya, or northern Mozambique.

Today Tanzania has what few other African countries have: a national language that’s spoken fluently by nearly everyone and binds the country together. Malawi and Uganda and Zimbabwe use English as a way of uniting their countries linguistically, and though widely spoken it’s not a first language for the vast majority of people. It’s not the same in Tanzania. Swahili is truly a lingua franca, spoken as a first or second language by nearly everyone, making communication possible, and joining together the countless tribes and ethnic groups to a common language and cultural identity.

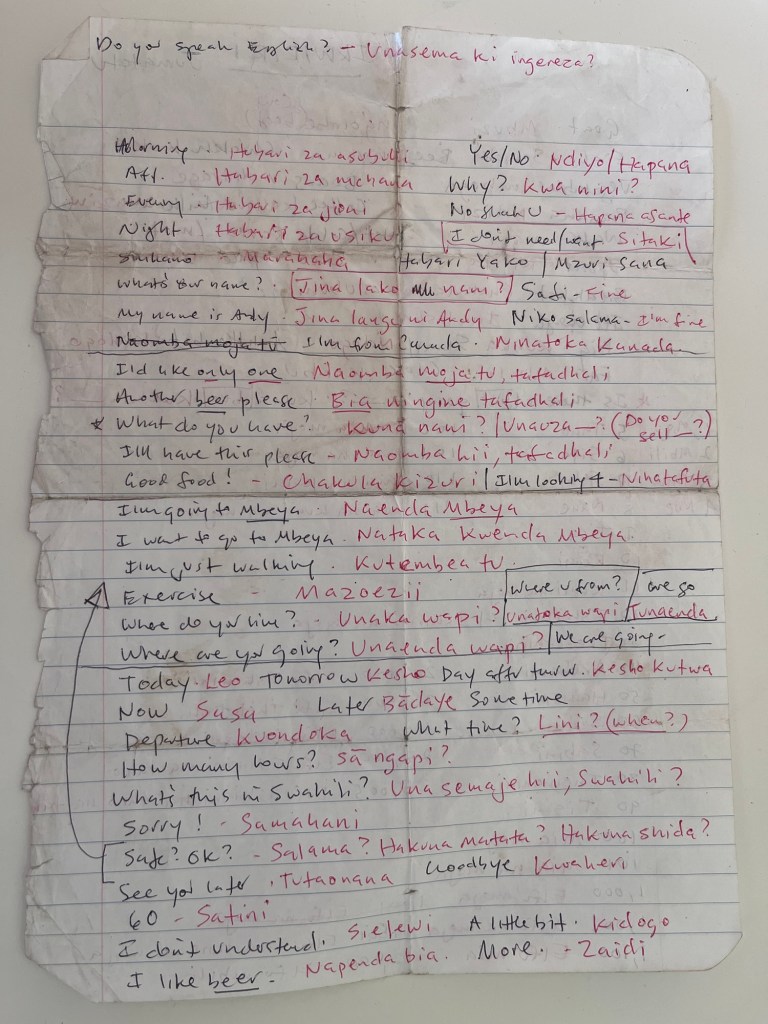

My Swahili cheat-sheet. I learned a lot of basic Swahili on this trip, and it proved invaluable in the south and southeast where English is not at all widely spoken.

I learned a lot of Swahili on this trip. It was fun and rewarding using the phrases and words I conjured up, and it proved absolutely necessary in the south where very little English is spoken, and where people were notably—sometimes very obviously—unwilling and unhappy to speak English.

I was surprised to find little to no mention anywhere along the Swahili coast of the region’s grim history of slavery. Local people speak a language and follow a religion introduced and influenced by the Arabs, who were there to enslave them and steal their elephant ivory; but there seems to be little awareness, or at least no presentation to visitors. In Ghana and Ivory Coast you come across slavery and colonial sites, as well as information on its history and resolution; but I saw virtually nothing in East Africa.

Dar es Salaam

Dodoma is the official capital of Tanzania, but Dar es Salaam is capital in all but name, and it’s where all the action is. There is plenty of sprawl, and there are rough and dirty neighborhoods, but “Dar” is far more developed and organized than other cities and towns in Tanzania. There’s definitely a whiff of sophistication and pizazz; you see a few Mercedes cars and well-dressed, stylish people eating in stylish restaurants. There are several sections north of town along the beach where you find smart apartment buildings, and large homes with leafy gardens. We’re not talking Monte Carlo here, and much of the city is still chaotic and rife with sprawl and pollution, but compared with mostly all of Zimbabwe and Malawi, and with the other towns in Tanzania, Dar is definitely where it’s at.

A busy street in the colorful and chaotic Kariakoo district of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania’s largest city.

One of the many Indo-African cafes and restaurants in Dar, providing a welcome respite from the traditional local food.

Dar has a population close to 6 million. There is tremendous sprawl and several large shanty towns, but many of the central districts are more orderly and calm. Much of central Dar reminds me of Mumbai, or parts of Hong Kong.

The Kariakoo district of Dar. Commerce, chaos, construction, and crowds is the rule of the day.

With the assistance of a Turkish engineering firm, Tanzania is building a new standard gauge railway from the coast at Dar to Mwanza on Lake Victoria, which I took between Dar and Morogoro. It was easily the most organized and “fancy” thing I saw in the country (I didn’t visit the airport).

The brand new Turkish-built standard gauge train ready to leave the brand new Dar es Salaam central station. I took the train on its 2-hour journey from Dar to Morogoro. The train and station were the fanciest, most modern things I saw in Tanzania, and appear to be extremely popular—at least so far.

There’s a large South Asian diaspora in Dar, mainly of Gujarati Indian origin. Many of the shops and restaurants are run by people of Indian heritage, ensuring the very, very, very welcome addition of Indian curries and breads to the otherwise very, very, very tired retinue of local cuisine.

Getting Around

Public transportation in Tanzania is far better organized and reliable than in Malawi or Zimbabwe. It can still be highly uncomfortable and slow, but there are more buses and minivans plying regular routes on what you might almost call a schedule. There are fewer shared taxis and informal rust-buckets trolling for customers. Most towns have some sort of a central bus station, or departure area, making it possible to get information on actual departure times and locations, which came as an unbridled luxury after battling the informal mess in Malawi.

Riding the bus between Songea and Njombe. Transportation in Tanzania isn’t fancy, but it’s a lot better organized and sensible than in Malawi.

Standing room only. On the “Coaster” bus from the Malawi border to Tukuyu, my first stop in Tanzania.

Tanzania has a fairly robust oil & gas industry. The government introduced a fuel subsidy in 2022 to help protect consumers from rising energy prices. Gasoline is much cheaper than in neighboring countries, allowing for lower transportation costs and, more importantly, less crowded buses and minivans: operators don’t feel they need to fill their vehicles to the rafters before they can start moving.

The Chinese are building a large bridge across the Mwanza Gulf, which is nearly finished. In the meantime all vehicles are loaded onto flat-bottomed barges for the short journey across.

Buses are better organized and reliable in Tanzania, but that’s not to say they never have problems. This breakdown on the bus to Biharamulo was sorted out quickly and we were back on our way.

The bus stand in Mbamba Bay. Not busy, but reliable.

Some passengers are too stinky to ride inside. These fish rode the wiper blades on the three-hour ride from Mbamba Bay to Songea.

Hitchhiking

Despite the sunnier climate for public transportation, I hitchhiked more in Tanzania than I did anywhere else. There are several large coal deposits in the south, near Songea, and I quickly noticed a nearly uninterrupted string of large coal trucks moving up and down the A19 road, taking trucks loaded with coal to the Indian Ocean port at Mtwara, coming back empty to get more (the Songea Karoo belt is managed by the Chinese; in September 2011, the Chinese government announced that it would run the Songea Karoo belt after investing $400 million in the project.) Every 10th vehicle seemed to be a truck, and most of the drivers were bored and only too happy to pick up aging white guys with backpacks standing on the side of the road. The trucks were heavy and moved much more slowly than buses and minivans, but they were far safer, and far more comfortable. It was extremely useful for Swahili practice, and was fun and adventurous.

Hitching a ride in one of the many coal-laden trucks running to Mtwara port from the coal fields near Songea.

Fearless Canadian hitchhiker making friends on the road.

A Few of My Favorite Things

I really loved hitchhiking in the south. It’s a region of the country that’s seldom visited by other Africans, let alone Canadians. The string of towns along the A19—Njombe, Songea, Tunduru, Masasi, Nyango—can all only be described as shabby, but they’re the real deal, where people are friendly and welcoming, and where I was able to experience an authentic, unvarnished version of modern-day Tanzania. The rhythm of hitchhiking, getting out of the truck, wandering around to find lodging and food, sleeping, getting back on the road the next morning was exciting and rewarding. I felt free, and full of energy.

Walking on the roads in Njombe. Overall the roads in Tanzania are much better than in Malawi and, especially, Zimbabwe.

Market street in Songea. It might not look it, but despite muck and potholes, many of Tanzania’s small towns are fairly well looked-after and better developed than in neighboring countries.

I also really liked the small historic coastal Swahili town of Mikindani, with its crumbly white washed buildings, palm trees and crooked, winding streets. There’s a fascinating old town with an interesting blend of local and Arabic influenced architecture, now registered as a National Historic Site. Before the Arabs arrived and established a slave market, Mikindani was settled by the Makonde people. Arab buildings from the 17th century still stand in town, and there are old graves and mosques from an earlier age.

The historic coastal village of Mikindani, one of my favorite places in Tanzania. The historic section of Mikindani is registered as a National Historic Site.

There are still many old colonial buildings scattered around Mikindani, making exploration fun and interesting.

A lazy late afternoon in Mikindani.

A Few of My Less Favorite Things

Nocturnal noise was a big problem in Tanzania. Despite the ubiquitous Muslim influence (around 35% of Tanzanians identify as Muslim), bars and clubs feature heavily in mostly all towns and villages, and with bars and clubs comes ear-splitting music well into the night. As in Malawi and Uganda, I was puzzled as to why the local town councils allow bars to blast their music so loud, and so late into the night. It’s understandable if your bar is in a suburb, or in the outskirts of town, or in a commercial or industrial zone; but there were small bars smack-dab in the middle of family residential neighborhoods. Most bar patrons were men (and prostitutes), but occasionally you’d find couples and groups of younger women sitting at tables all utterly unable to hear each other. It was a mystery to me, and cost me a few lousy sleeps. That’s not to say I didn’t enjoy the bars—I did, Tanzanians know how to drink—I just wished the enjoyment only lasted until 10:00 p.m.

Enjoying a cold bottle of Kilimanjaro Premium Lager in Songea before the evening crowds and noise arrived.

People

Tanzanians are very welcoming, courteous people, just like most East Africans. I was always treated with respect and politeness, and many people were very interested in me and made a point of waving or stopping to say hello. As usual, kids in particular were jolly and energetic. English is far less widely spoken in Tanzania, which made it more challenging to learn about daily life and customs (my Swahili vocabulary was largely restricted to phrases concerning directions, food items, numbers, and greetings), but it was obvious that I was welcome and made to feel comfortable. Locals in Dar es Salaam were much less interested in me, but that’s just because it’s a large, more international city.

Two junior members of the Mwanza Welcoming Committee.

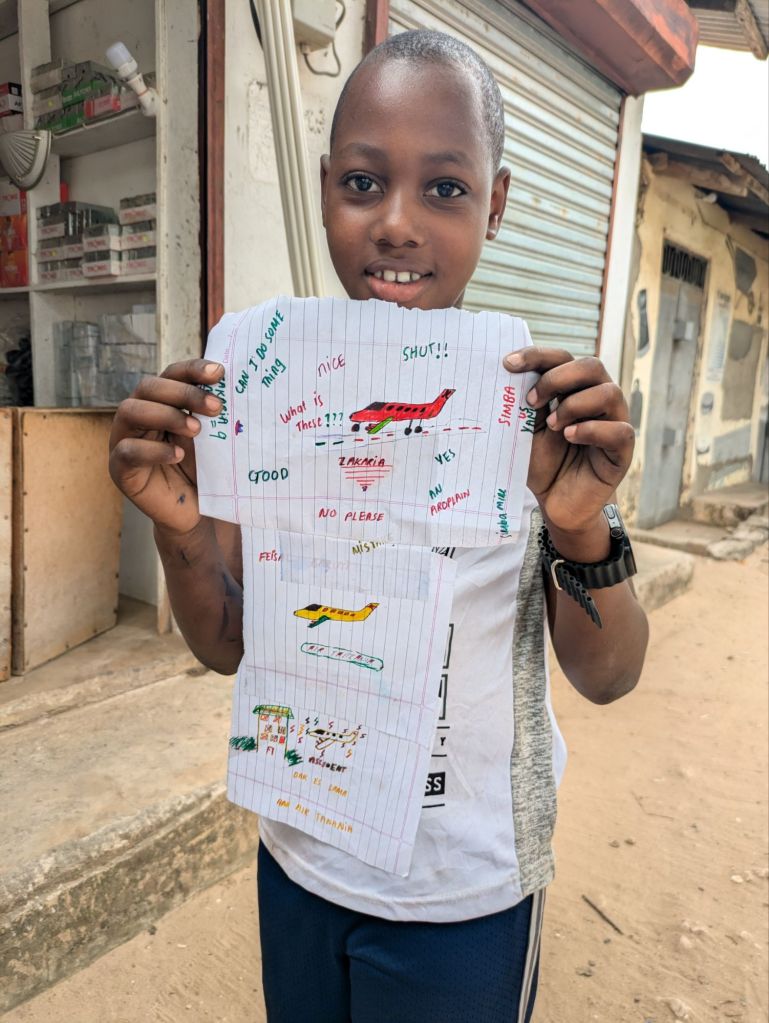

This young lad lived close to my hotel in Kilwa Masoko and was learning English. I asked him to draw me a picture.

Kids in a village during a long walk out of Biharamulo.

I did occasionally notice a slight bristle when I tried to speak English, which was mostly all the time. I could greet people in Swahili, say hello and ask how they are, and I could ask for a room and ask about the cost, but after that I had to switch into English. Most of the time it was fine, though not many people spoke it. But there were a few instances where I tried to speak English right off the bat, and got a “No English. Swahili,” reply. A few people told me they didn’t speak English, then continued to say (in English), “This is Tanzania. We speak Swahili.” Which is completely reasonable. I like to learn local greetings anyway, and in almost all cases I began any interaction with a Swahili greeting. I did the same in Malawi, with Chichewa, where it almost invariably resulted in smiles and giggles. Not so in Tanzania. I spoke Swahili, they spoke Swahili, and that was that. I assumed it was an issue of nationalism and pride, and nothing to do with me or where I came from. It was a good reminder to be respectful and courteous to people when you find yourself in their country.

A woman walks down an alley in Songea. You can see a group of men watching a soccer (football) game in a small coffee shop.

My lunch lady at a large outdoor food court market area in Dar es Salaam. The variety of food in Dar was a welcome relief.

Accommodation

There’s plenty of accommodation in Tanzania at the budget level, mostly all of it excellent value. I was routinely surprised and pleased by the rooms I found. 30,000 shillings (around $11.50) got you a basic room with a bed, attached bathroom, often with hot water, ceiling fan, mosquito net, and sometimes a table and chair. The rooms were always clean and bright. I got a couple of dirty clunkers, but only a couple, and considering I was there for 33 days, I did very well. I never felt insecure in any of the rooms, and had no issues at all with theft or nosy staff.

My room in Mbamba Bay. There was very little variation in the budget rooms in Tanzania: a bed, clean and fresh sheets, a mosquito net (often with holes), ceiling fan, and a chair or little table. Rooms like this are cheap, ranging between $8 – $12.

Most rooms came with attached bathrooms. This one in Tunduru was a little fancier than most.

As I mentioned above, noise was a problem. I became very vigilant to hotel location. Before even inquiring I’d wander around the neighborhood to see if there were any nearby bars. A couple of times I found myself in a town with only one hotel—right beside a bar, of course—so didn’t have a choice. It was handy for grabbing a few cold beers, but not handy for my beauty rest. But there was nothing to be done about it, it just comes with the territory.

Starting early – a busy outdoor bar in Tunduru welcomes locals with nothing else to do on a lazy Sunday afternoon after church.

Food and Drink

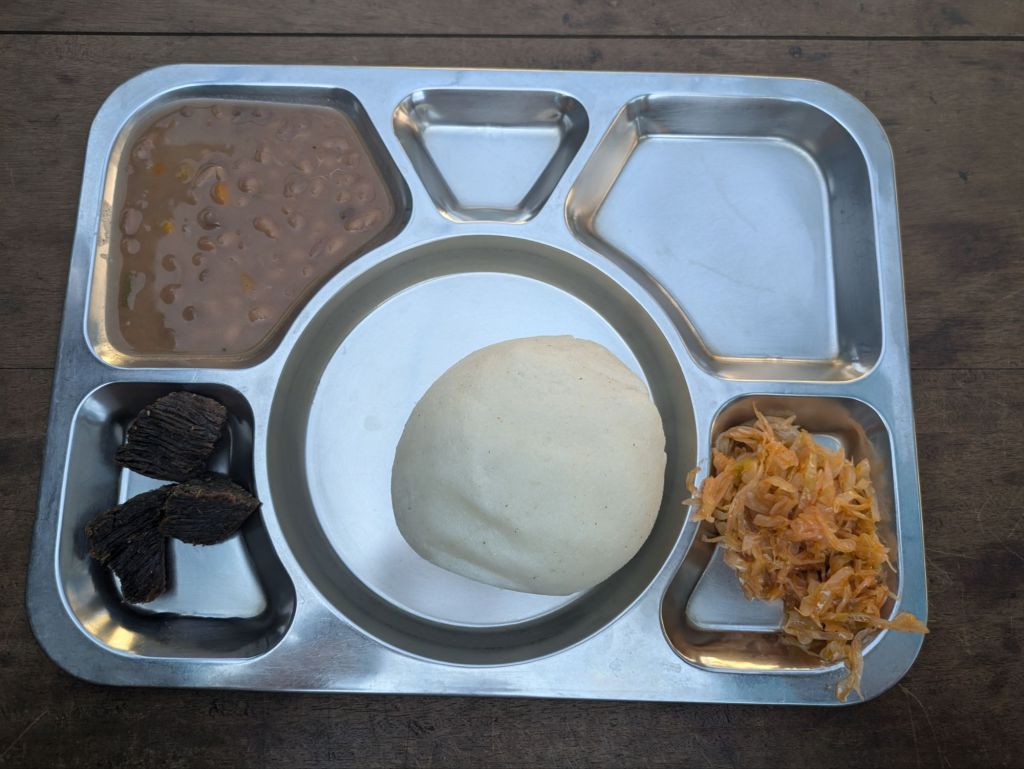

Food in Tanzania is a little better than the stuff in Malawi and Zimbabwe, but only a little. The Arab-Swahili influence adds a little zing to some of the food you find along the coast, and the fish and other seafood can be good (though slightly expensive), but in most regular places you get the same sort of selection you find in Malawi and Zimbabwe. The white pounded maize porridge-dumpling staple is called ugali in Tanzania, and it might—and I do mean might, here—be slightly tastier than what you find in Malawi or Zimbabwe. Goat, chicken, fish and beef dishes are very similar to those in Malawi. A few of the vegetable sides in Tanzania aren’t bad, especially tomatoes, onions and stewed greens. There is excellent Indian food available in a few of the larger cities, most notably Dar es Salaam, where there’s a very sizable Indian diaspora dishing out hot thalis, samosas, chai and biryani.

Food in Tanzania is similar to the stuff you get in Malawi and Zimbabwe: a big blob of ugali (cornmeal porridge/dumpling), and a few sides, in this case beans, mustard greens, and a tomato/onion salad. Food is a bit dull, but in fairness, almost always fresh and hot and clean. This meal was enjoyed in Njombe.

Lunch in Mabamba Bay: ugali, cassava leaves, and little sardine-like fish. Meals in Tanzania were comically cheap, usually not much more than one dollar.

The Michelin Star people don’t spend a lot of time looking for hidden gems in Tanzania…this lunch in Morogoro was memorably bland, and short on presentation.

At the food market in Dar es Salaam. Almost all cooking is done on wood or charcoal fires.

Coffee was mostly excellent in Tanzania, and it was a relief to find so much of it. People drink coffee in the streets, usually poured into small cups by young men or boys who brew large pots over charcoal fires, then transfer it into smaller thermoses and disperse it in cup after cup to (mainly) men who gather at street corners or under trees to socialize and drink. It’s ludicrously cheap at just a few cents a cup, and is widely available, especially along the coast and in Dar, where there’s the strongest Arab influence. There are always simple snacks to go with your coffee; coconut peanut brittle was my favorite.

A cafe in Songea where I stopped for a not bad cup of coffee and a sort of donut.

Beer is readily available nearly anywhere in Tanzania, mostly lager, and it’s quite good, and incredibly cheap. Local brands Kilimanjaro, Safari, and Serengeti are by far the most popular, but you can often find Kenyan Tusker brand, as well as Guinness and Twiga stout. A lot of Tanzanians like their beer warm—yuck—but luckily it’s also available cold. When you order the bartender always asks if you want it warm (moto), or cold (baridi). Baridi was probably the first word of Swahili I learned.

Some people just can’t handle the Samaki Samaki pub in Kilwa Masoko.

Costs

Traveling in Tanzania as a local, away from the tourism hotspots is cheap. I routinely found excellent, basic lodging for between $8 – $12, except in Dar es Salaam where offerings at the cheap end of the scale are extremely rough. I paid $26 a night for a good room at the Sophia Hotel in Dar. Tanzania can be very expensive if you stay in luxury lodges on the safari circuit, or in boutique places in Zanzibar, but in the normal everyday towns, basic lodging is cheap.

Simple local meals at basic stalls or small cafes were nearly always one dollar, or $1.25. Large green, sweaty 500ml bottles of local beer cost $1, and a bag of fruit and veg almost never costs more than a couple of dollars. Tanzania has its own oil & gas industry, so gasoline was a lot cheaper than in Zimbabwe or Malawi, which resulted in lower transportation costs. Cash is easily available from ATMs found in essentially every town larger than a village. I spent on average between $15-$20 a day for everything, which is terrific value.

A group of school children make their way home on the back streets of Ikwiriri.

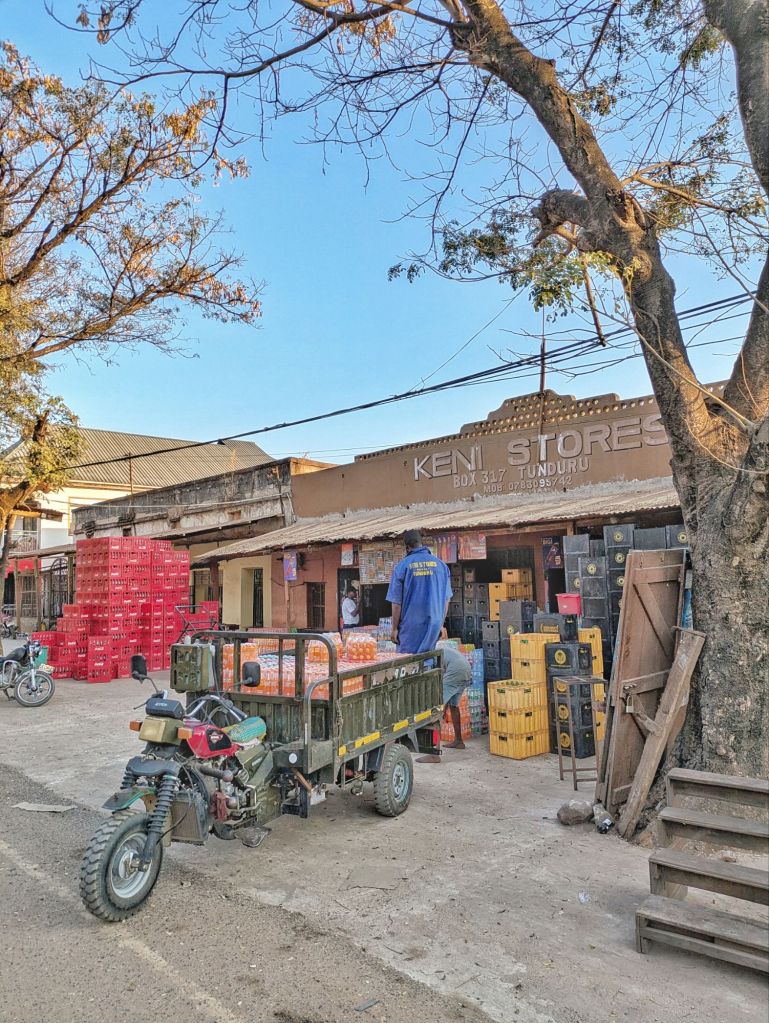

Loading up a delivery at the Keni Stores in Tunduru. There’s a lot more noticeable commercial and business activity in Tanzania than in Malawi or Zimbabwe.

The Verdict

It would be a very tough call, but if pressed I’d have to say Tanzania is my favorite African country. At the moment. It’s close, though: Uganda is a close second, and used to be my favorite. Malawi is right there in the running, too. But Tanzania has a slight edge on variety (largely because of its size), and because of the interesting and distinct Swahili culture. Malawi and Uganda have many different tribes and cultural nuances, but they don’t have anything that I’m aware of that’s as mixed and jumbled in such an exotic and distinct way as the Swahili culture.

I’d love to visit Tanzania again, and already have several routes and districts in mind. Here’s hoping.

One of the many backroads through the Tanzanian countryside, this one outside of Mbamba Bay. I loved going for long walks on these kinds of roads. East Africa is right up there with some of the best.

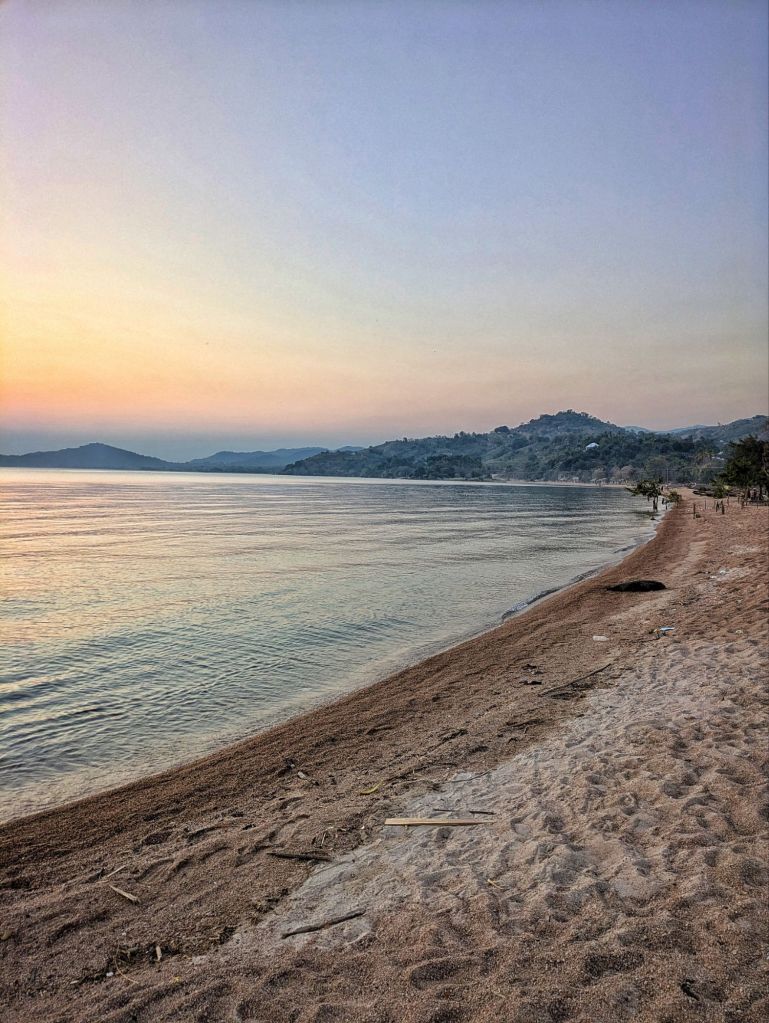

A beach at Mbamba Bay. Mbamba Bay is on Lake Nyasa in the far south of Tanzania. Not far across the lake is Malawi, where I’d just come from, and where the lake is known as Lake Malawi.

Market activity in Biharamulo. It looks as though these women are arguing, but they weren’t; just swapping stories, I think.

If you missed the first two posts in my Africa series, on Zimbabwe and Malawi, you can find them here. Next up is Uganda. In the meantime…

Stay Tuned!

* Remember! I love receiving comments, but anything you write, including when you hit “Reply” to the email notifications, is public. You know who you are…

* If you liked this story why not read some of my other blog posts? They’re all here.

* If you liked this post, why not subscribe? Sleep easy knowing you’ll never miss another story. Click on the “Follow” button, or contact me and ask to be put on the list.

* Follow me on Instagram, if you’re bothered. I’m @arjwilson.

“You should travel to learn about countries and the way normal people live in them, not to see the spectacular things. Buy vegetables, get a haircut, explore a suburb, walk out of town. Don’t look for the special, look for the banal.”

Discover more from The Plain Road

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Having read Malawi and now having read Tanzania, I’m thinking Malawi might be a better starting place. The inceased understanding of English in Malawi would provide the possbility of deeper conversations???

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thoroughly enjoyed reading your account of your travels there Andrew.

The A19 looks like it was fun.

And good that are ‘still’ up for a challenge like that 🙂

I thought you might like Kariakoo. I did too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another excellent account. You have yet to disappoint

LikeLiked by 1 person