I left Peru and headed for Bolivia, the main target in my South America overland trip. This is the second in a series of blog posts on the South American countries I visited between January and June, 2022, though not in order).

Bolivia was the main target on this South America trip. Reading about it in advance I developed the idea it’s the most exotic and indigenous and wild looking of the South American countries. It’s true, it is exotic and indigenous and wild looking. But what I didn’t realize was that Peru and Ecuador are also exotic and indigenous and wild looking, and that while Bolivia was all I’d imagined and hoped, it didn’t necessarily stand head and shoulders above any of the other places. If I was forced, I’d choose Peru as my favorite, but that doesn’t mean Bolivia isn’t fantastic. It really is. It’s almost impossible, but I’d have to say the scenery is even more dramatic than in Peru, and there might be even more visible indigenous culture. Bolivia is smaller than Peru but it really packs a lot in. I’m definitely going to return.

Like in Peru, there’s a standard “get in, get out” itinerary that most foreign visitors follow: cross the border from Peru (usually from Cusco) and go to La Paz. Go north from there to ride a bicycle down the “Death Road”, then go south to the Uyuni Salt Flats, maybe visiting Sucre or Potosí along the way, then cross the border to Chile, or fly out to somewhere else. Outside of those places the country mostly isn’t set up well for foreign travelers. You need to speak and read Spanish, and you need a lot of time to get around and search for places to stay. I bumped into other independent backpackers here and there for sure, and in some cities there are plenty of Bolivians seeing their own country, but they’re mostly weekend trippers to churches and markets, not longer term overlanders.

I saw quite a few foreign travelers in La Paz, and bumped into a few here and there at bus stations in Sucre and Potosí, but outside the main areas I was largely on my own.

The pretty central plaza in Sucre.

Getting In and Out

I arrived in Bolivia overland from Peru on May 1 and spent 29 days in the country. The small Bolivian immigration office in Desaguadero is tatty and old and crowded, though it only took a little under an hour to complete the formalities and enter officially. I accidentally wandered about 200 meters into Bolivia before realizing I’d passed the office and had to return. I could easily have just carried on, though when I eventually left the country with no entry stamp the jig would have been up. Still though, it was all pretty casual.

And I dodged a real bullet on getting in: the Bolivian government was still asking for a negative PCR test result for entry right up until two days before I was planning to arrive, but they scrapped the regulation the day before so I waltzed in with just my passport and a smile. Most tourists are given a free 30 day visa upon entry which can be extended twice.

I left Bolivia from Bermejo in the far south, crossing the Bermejo River into Argentina in a little tippy motorboat along with scores of other Argentinians and Bolivians who cross regularly for commerce, shopping, and work.

Waiting for their turn in the boats to cross the Bermejo River into Argentina, visible on the other shore.

And in Argentina, looking back at Bolivia.

My Route

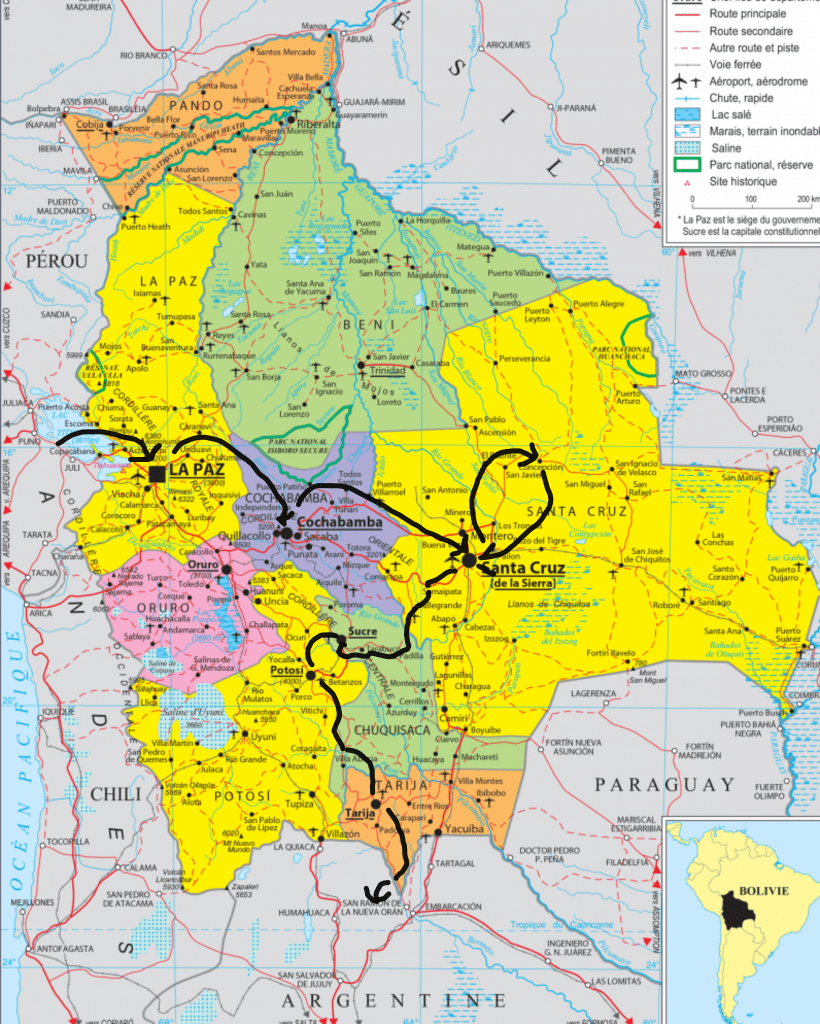

From the Peruvian border I went the short distance to La Paz, the magical and captivating commercial and de facto capital of Bolivia that sits in a bowl nearly 4,000 meters above sea level (the political and official capital is Sucre). From there I went east to Cochabamba department (or, province) and spent time visiting a few of the little market towns in the area. Then I headed to Santa Cruz, Bolivia’s largest city and business and trade center, hot and steamy at a much lower altitude, and full of bustle and energy. Next northeast into the Misiones region, so named for the early mission churches and sanctuaries the Spanish Jesuits established shortly after initial colonization. I backtracked to Santa Cruz for a few nights then started a nearly week long odyssey between Samaipata and Sucre on back roads, a true South American adventure. From there I went south to the Argentinian border stopping in Potosí, Carmago, Tarija and Bermejo.

When I look back at my journal and the route I took through Bolivia what stands out now is how small a portion of the country I actually saw. I feel like I saw a lot, and spent nearly an entire month there, but seeing the map now it’s striking how much I left on the table. Seed for the next journey, I suppose.

Getting Around

Moving around in Bolivia was very similar to moving around in Peru. I traveled by bus, minibus, minivan and shared taxi, and I hitchhiked on a few of the routes (which was fairly easy). Finding transportation is quite the same exercise as in Peru, too; you have to ask a lot of questions until you find out which bus companies go where, when, and from where, though I’d say there are more central bus stations/departure points in Bolivian towns than there are in Peru. The busier main routes are easy enough, but the usual detective work is required for the out of the way trips. And I like the out of the way trips. People always knew how to get to the towns closest to them, but were rarely sure about moving on farther from those towns. Truck drivers almost always knew, though they tend to stick to the main, faster routes so you can’t always rely on them for information. Truck drivers were the only people who picked me up when I was hitchhiking.

It’s not formal or high-tech, but at least this bus station in Cochabamba had a schedule; many don’t.

Just some of the fantastic scenery in Bolivia; this is between La Paz and Cochabamba.

On the road somewhere in the mountains. Bolivia isn’t very densely populated, so there are lots of open spaces.

On the Road in Bolivia

Despite there being a well-trodden gringo trail through Peru, I actually saw more western travellers in Bolivia. I was initially surprised at this, as I’m pretty sure Peru sees many more tourists annually than does Bolivia, but when I thought about it, it made sense: I didn’t really go anywhere in Peru where there were tourists (I missed Machu Pichu and the Sacred Valley, the main draw), and there are fewer places to go in Bolivia—the country is smaller, there are fewer roads and fewer options to move from place to place—so the tourists that are in Bolivia bunch up, they’re more concentrated. I didn’t go to the famous Uyuni salt flats to get the coveted Instagram selfie, where it would appear the vast majority of tourists go, so I don’t have a clear idea of numbers in Bolivia overall, but the post-Covid travel wave was definitely underway when I was there. La Paz had the most visitors, which makes sense.

The landscape and climate in Bolivia can be wildly different from province to province, and the variety is one of the main things that makes Bolivia such an exciting place to travel. La Paz and its outlying towns and districts sit at around 4,000 meters, but Bolivia has a large chunk of Amazon rain forest as well, in the province of Beni, which is low and hot and steamy. The high Altiplano (the Andean plateau) is a stark, windy and cold place. Then there’s the eastern lowlands, which are green, hot and humid, anything but stark, windy and cold.

Strolling the main plaza in Sucre.

The south of the country, in Chuquisaca and Tarija provinces, is cowboy country, arid and brown, studded with cactus and adobe houses. It’s where Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid ended their outlaw days. Santa Cruz in the eastern lowlands is the largest of Bolivia’s 9 provinces, stretching all the way to the border with Brazil and making up a third of the country’s overall territory. It’s also hot and humid and largely agricultural, producing sugar, cotton, soybeans, and rice. The capital of Santa Cruz, also called Santa Cruz, is the largest city in Bolivia with a little over 3 million people (La Paz has around 2 million).

Whichever direction you go in Bolivia you don’t need to go very far before everything starts looking different. Traveling around the country is slow going, but the changes in scenery and climate are dramatic.

I found independent travel in Bolivia to be slightly more difficult than in Peru, mainly (I think) because there are fewer people and fewer roads, and the terrain is challenging. But I loved traveling in Bolivia, I loved the challenge and the variety.

The dusty back streets of Samaipata.

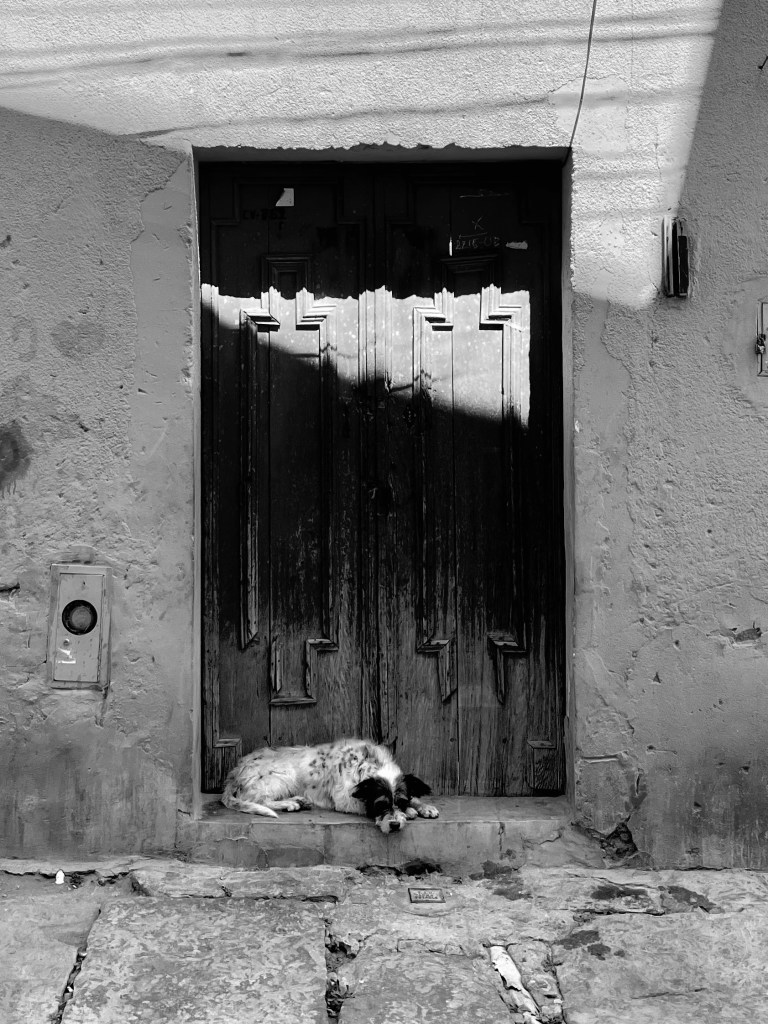

Siesta time for the hard working dogs of Samaipata.

On the road between Sucre and Potosí.

Bolivia is the second poorest country in South America (after Venezuela, apparently), and although I didn’t see the bone crushing sort of poverty you find in Bangladesh or India, or in West Africa, you can tell it’s not a wealthy place. Mostly all the cities and larger towns have very clean and tidy, attractive and well maintained central downtown cores—Sucre and Cochabamba are good examples with their beautiful plazas—but when you wander away from the central areas, and in many of the other smaller towns and villages you find very poor infrastructure, and the neighborhoods can be dirty and uncared for, with a lot of unfinished rough cinder block buildings and garbage in the streets.

I’m not sure this would be my first choice for a dentist…

People rely on government services and aid organizations where they can, but to a large degree, they’re on their own, making do the best they know how. It’s the same thing I’ve noticed in many other developing countries, and is an enigma: I know on paper how poor, unjust, unfair, unequal and pessimistic life in those countries should be, but people mostly carry on, and they’re mostly cheerful and optimistic, on the outside at least. You do what you have to do to live, I suppose.

There are around 12 million people in Bolivia.

My Favorite Places

That’s easy: La Paz. It’s an amazing place, visually stunning and extremely interesting. It’s not a massive city, (there are just under 2 million in the greater La Paz region), but it’s very colorful and alluring with its high altitude setting and snow-capped mountain backdrop. As with all cities in South America (or at least the ones I’ve seen) you find the usual selection of different parts of town: there’s a rough and tumble area, a rich area, a middle class area, a business district, a few market areas…but in La Paz they seem to be closer together than usual, the transition from place to place very sudden and unexpected. You might be wandering up a hill lined with kitchen and bathroom shops, crest the hill and find a sprawling vegetable market dropping down the other side, or a long queue of people waiting to get into a nondescript government ministry, or a lone shoe repair man working on the side of the road.

A typical street scene in La Paz; the streets are always colorful and busy.

Plaza Morillo, in the historic center of La Paz.

Meat stall, La Paz market.

Many of the streets in La Paz host informal markets like this one in the San Pedro neighborhood.

The markets are terrific, extremely colorful, and filled with an enormous variety of, well, everything. La Paz—and Bolivia as a whole—has a very high concentration of indigenous people, mainly Aymara and Quechua, who wear their own clothing and speak their own languages, many of whom set up temporary market stalls in the streets and on the sidewalks, calling out to passers-by.

There is a pretty historical center, with the usual cathedral, plaza and municipal buildings, and some interesting colonial architecture, but the real beauty and attraction of La Paz is, for me, in the color and the way the city unfolds itself across the mountain-top hills and valleys in so many different layers.

Plaza Mayor de San Francisco, central La Paz.

The coolest thing about La Paz are the teleféricos, the cable cars that zip up and down the hills and mountains. Visitors to other Latin American countries will have seen teleféricos in Medellín, Guayaquil, Mexico City, Rio de Janeiro and Bogotá, but La Paz has by far the largest network, with 32 kilometers of cable making up of 10 lines, and linking 37 stations.

They’re designed to connect the higher areas of the city with the lower areas of the city, a difference in altitude of more than 500 meters, saving hours in commuting time, and offering a cheap and safe alternative to the deathtrap passenger minivans that careen through the streets. The technology and construction of the system comes from the Austrian engineering company Doppelmayr.

Riding the teleférico in La Paz, by far the coolest thing to do in town.

I wasn’t living or working or commuting, of course, so my main interest in using the teleférico was for recreational purposes. They’re fantastic! The views from the gondolas are breathtaking, offering a 360 degree bird’s eye view of the entire La Paz region. The ride is cheap (about .40 cents), and the distance between stations on some lines is enormous, allowing you to enjoy the ride for up to 20 minutes at a stretch. Once at the end of the line you can transfer to another one and keep going. Gondola cars depart every 12 seconds, and the network is open 17 hours a day.

I quickly discovered it was rewarding to ride the same lines at different times of the day so I could enjoy the changes in light and color, and the quiet and peace afforded inside the cars. Twilight was a favorite time of day, when I could watch the city come to life through the lens of twinkling lights that shined over a backdrop of a fading orange and red sunset. I was often alone, but many times shared the cars with fellow passengers, some of whom were very chatty. I spent over 15 minutes listening to a middle aged man dressed in an old suit caution a young woman to be on her lookout for liars. I couldn’t understand everything he said, but got the general idea, and even managed to ask him a question, which he was happy to answer (the young woman seemed relieved).

Dusk settling over La Paz.

The electric light fixture section of one of the street markets in La Paz.

Another of my favorite places in Bolivia is Camargo, way down in the south of the country in Chuquisaca province. I liked it mainly because of how utterly different it was from anything else I’d seen in Bolivia, and how charming and friendly the town’s people were. It’s a small place of about 15,000 but set in the most fantastically colorful area of cactus, adobe houses, and wild west scrub land. I arrived there from Potosí, a largely treeless, windswept high altitude wasteland which made Camargo all the more dramatic. Camargo is not a place tourists stop—I got a lot of looks and noticed double takes when I wandered around town—and there’s nothing particularly noteworthy about the place, but I loved the contrast and the scenery, and the quiet, unassuming everyday normality of the town.

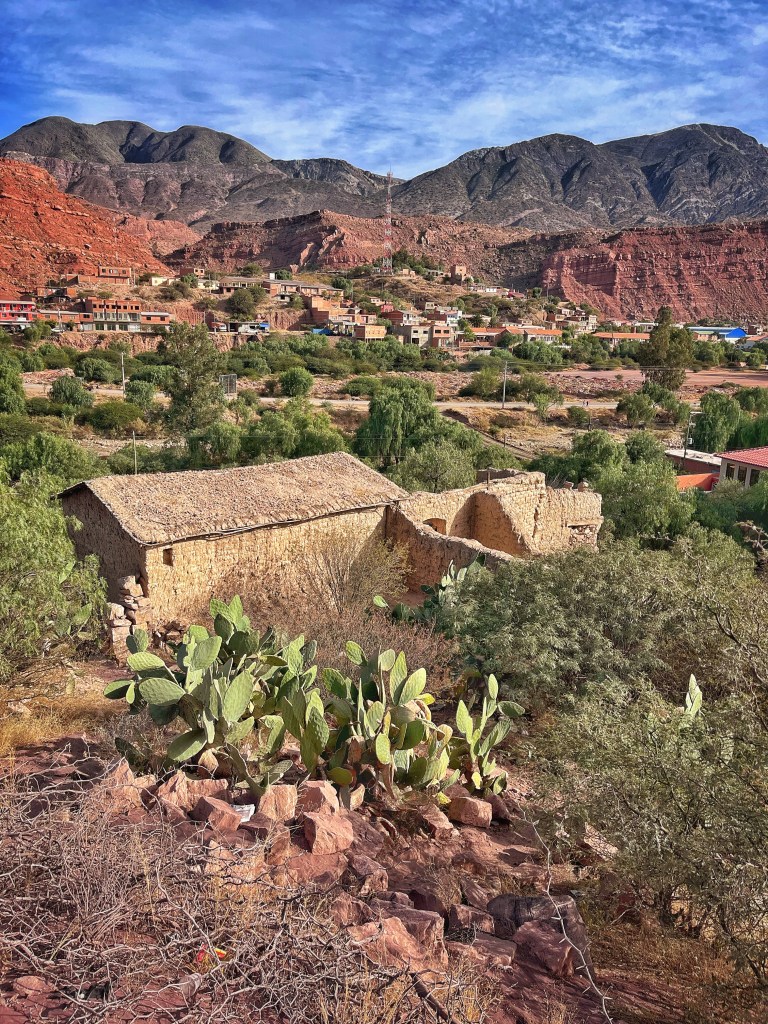

The cowboy scenery in Camargo. Camargo was one of my favorite places in Bolivia.

The Copacabana Bar and Restaurant in Camargo, sadly closed when I was in town.

Cochabamba province is also close to the top of my list. The capital, also called Cochabamba, has one of the most attractive colonial central plazas in Bolivia, and the food is excellent. I based myself in town then made a few day trips to nearby villages when it was their turn to host the regional weekly markets. The little villages were around 45 minutes to an hour away from the city, and offered the opportunity to see authentic out-of-the-way Bolivia, and to sample local food and chicha, the local indigenous corn alcohol.

Drunk since the days of the Inca, “chicha” is a light alcoholic drink fermented from corn. The Cochabamba region is known for its excellent chicha, so naturally I was forced to try it several times.

Chicha seller at the market in Arani, Cochabamba. A large plastic jug costs just 4 bolivianos, around $.56 cents.

Chilling with the locals over a jug of chicha in Arani.

One of several busy and colorful markets in Cochabamba.

When I return to Bolivia I’ll spend more time in Potosí. I was only there for two nights but found it very interesting and exotic. It is one of the highest cities in the world, perched in an empty plain at 4,090 meters (13,420 feet). For centuries, it was the location of the Spanish colonial silver mint, primarily because it’s home to the Cerro Rico de Potosí (“The Rich Hill of Potosí”) the world’s largest silver deposit, a massive outcrop lording over the city to the west. It’s been mined since the sixteenth century, and is still being mined. At night you can see a long train of hazy lights move up and down the mountain as trucks grind their way from the mines to the valley below.

The near Martian landscape above 4,000 meters in Potosí. It was cold and windy the two days I was in town.

The stark scenery in the high Altiplano, near Potosí.

Also known as the Chiquitos, the Misiones region in the east of the country was also a highlight. The missions were founded by the Spanish Jesuits in the 17th and 18th centuries to convert local tribes to Christianity, but also to protect them from the clawing hands of the Spanish government. The missions were self-sufficient, with thriving economies, and virtually autonomous from the Spanish crown. When the Jesuits were eventually thrown out of the country in 1767 (by the Spanish crown, who felt the Jesuits were too independent and not sufficiently loyal to the court) many of the indigenous people, suddenly unprotected, were taken to work as slaves in the silver mines. The missions were abandoned and quickly fell into ruins, which ironically allowed them to remain untouched for hundreds of years and has ensured the settlements and their culture have survived largely intact.

The striking Jesuit cathedral in Concepción, in the Misiones region, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Most of the streets in Concepción are dirt. It’s a fairly low altitude region, so the days were hot and humid.

Several of the original churches still stand, and are now UNESCO Heritage Sites. They’re unique and very attractive. The Jesuits tried to be sensitive to indigenous art and design when they built them, and the result—to my eyes—is something that looks almost Polynesian, or Indonesian. Despite the UNESCO status the towns are extremely quiet and local and unvisited, at least when I was there, though I learned there are several large annual festivals that swell the towns with visitors.

Local kids playing in front of the Concepción cathedral.

The main square in Concepción on a quiet and calm overcast afternoon.

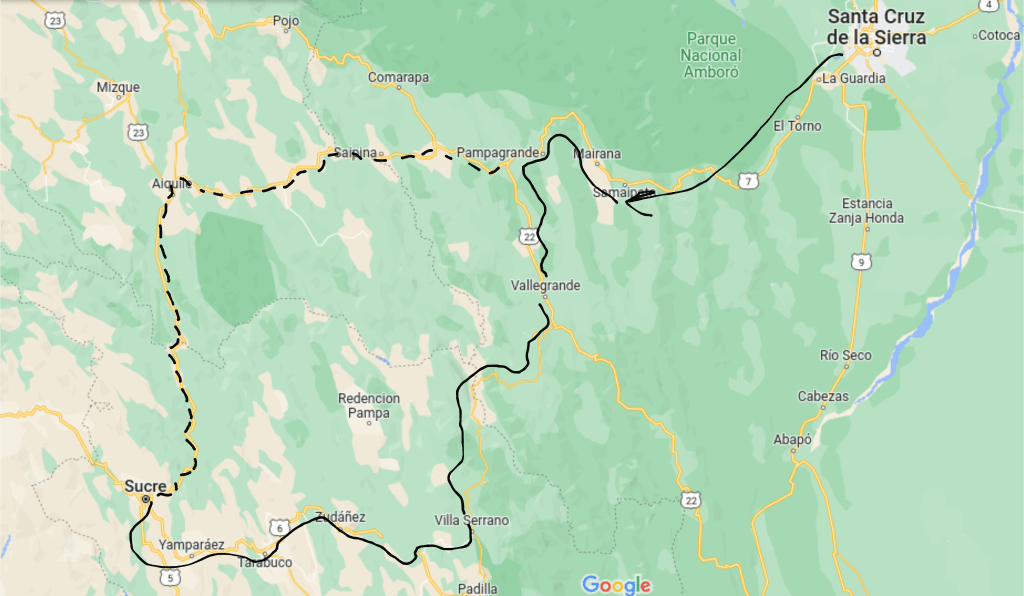

The journey between Samaipata and Sucre was fantastic. There’s a major road that runs between the town places (well, major-ish), but I chose to go another way, through Mataral, Vallegrande, Pucará and Villa Serrano, which took three days and involved a lot of waiting and standing around, and rattled loose several of my fillings along the road. Pucará is tiny, with no formal hotel, no restaurant and very, very little onward transportation. It’s set in a stunning mountaintop location, though, and was a highlight.

The usual route between Samaipata and Sucre (dotted line) takes 12 hours; my route through the mountains (solid black) took 3 days.

The pretty provincial town of Samaipata, as seen from my hotel window.

One of the many fantastic vistas you see traveling through rural Bolivia.

A blustery afternoon in Pucará, on the way to Sucre. Pucará is a tiny, isolated hamlet along the route that sees few foreign visitors.

On the road to Villa Serrano, a lonely, cold and out of the way back road if ever there was one.

Accommodation

On the whole accommodation in Bolivia offered similar standards, styles and prices to Peru, though I stayed in a few more guest houses in Bolivia than in Peru, homes where the family has carved out several hotel-like rooms around the back, or side, for guests. As in Peru I mostly found places to stay using Booking.com and Google Maps, then dug around for the hotel’s WhatsApp number and made a booking directly. There were a couple of towns where I didn’t find anything at all online, but a few minutes wandering around once I got there always flushed out something. Overall it was easy finding places to stay, and the quality and value was quite good.

My digs at the Hotel Media Luz, in Camargo. Accommodation in Bolivia was, for the most part, very good.

Not all the hotel rooms are as tidy and modern. This one was home for the night in Pucará.

The tiny but tidy little hamlet of Pucará.

It was cold in the mountains and Altiplano when I was in Bolivia, and a few of the places I stayed didn’t have hot water (or worse, had only warm water), so I had a couple of cold nights in bed in the fetal position wearing all my clothes. I eventually bought a warm, puffy jacket in the market in Samaipata which kept me plenty warm during the day and evening, and even kept me warm a few of the nights when I wore it to bed.

As in Peru I spent an average of between US$10.00 – $15.00 per night for a basic room with attached bathroom and toilet. Santa Cruz was the most expensive place, where I paid $26.00 for a room (it was a nice room though!), and Villa Serrano was the cheapest, where I paid just $6.00 for a very comfy single room.

Food

The food scene in Bolivia wasn’t anywhere near as good as in Peru, but it was still very decent. There wasn’t much ceviche (Bolivia is landlocked, perhaps a reason why), and there’s nowhere near the variety of dishes and ingredients, but the value was good, the portions sizable, and on the whole everything was very tasty. Chicken or liver or beef served with rice, potatoes, yuca (cassava) and salad was common. Fruit and fruit juices were excellent. The soups were usually excellent.

Sucre is known for its excellent chorizo, so I put it to the test myself (it was good!).

This was the best empanada I’ve ever eaten, served up fresh in the market in Villa Serrano.

In Cochabamba I tried Silpancho, a traditional dish notable for its huge size and ingredients that are heavy in fat and carbohydrates. You get a layer of white rice topped with boiled or steamed potatoes, beef or chicken cutlets, and fried eggs, garnished with beets. It stays with you all day.

The variety and quality of vegetables available in the markets was also excellent. Bolivia has better bread than Peru. There was very little street food in Bolivia, that I noticed. The coffee scene in Bolivia was, if possible, worse than in Peru (but still better than Paraguay!). Meals were cheap; a healthy, tasty and nutritious set-menu lunch meal usually cost only two or three dollars.

Potato seller, Cochabamba.

Fried dough and instant coffee for breakfast in Vallegrande. The coffee scene in Bolivia was more miss than hit.

A fish feed at the market in Arani, Cochabamba. A fresh fish with yuca, beans, potato and juice sets you back 2 dollars.

Nighttime street hamburgers in Tarija.

Frying up the fish at the Arani market.

Salteñas in Bolivia are outstanding, traditional fried snacks that are widely available. They’re little crescent shaped filled pockets of dough, similar to empanadas, or Indian samosas. Usually they’re stuffed with beef, pork, or chicken and spices, but I also found them filled with peas, eggs, potatoes, and olives. (I was surprised to notice some places serve vegetarian salteñas). They are always made fresh first thing in the morning; usually by 11:00 or 12:00 a.m. the salteña sellers run out and you have to wait for the next day’s batch.

The Bolivian salteña.

People

On the whole I found Bolivians very easy to get along with, friendly and helpful. As a generalization I’d say they’re slightly less warm than the Peruvians (and much less warm than the Colombians), and they tend to keep a little more to themselves. I could sit on a bench in a public park for an hour without a single person approaching me, something that usually didn’t happen in Peru or Colombia, where eventually a local would approach to say hello, or to ask me a question. But Bolivians were always happy to chat with me when I spoke first.

Locals enjoying an empanada and a glass of api in Potosí. Api is a thick, slightly sweet corn-based drink similar in texture to buttermilk or yogurt, and it’s delicious. Purple api is also very common.

Local Quechua women taking a pig to market in Sipe Sipe (I’d say it was fairly unlikely the pig returned home at the end of the day).

Typical rest stop for long distance buses; these passengers were lined up to buy home-made ice cream.

A group of school kids I met on a hike near Cochabamba. They were shy, but polite and interested in talking with me.

A street side shoe repairman at the end of the day in Potosí.

Merchants and shopkeepers were very pleasant and courteous, and I don’t think I was ever overcharged or swindled (I was mostly not in touristy regions, which could be one reason why, but I think it’s more because the average Bolivian is honest). The only area for caution was related to counterfeit currency. Apparently the forgery of banknotes is a big problem in Bolivia, and everyone is on guard for fakes. Before a shopkeeper accepts your 20 boliviano note he’ll run through the standard checklist of scratching to make sure it’s real, holding it up to the light, folding it, and wrinkling it.

One day I bought bread from a woman street vendor, and discovered later when I tried to use the change she gave me that I had fake bills. I didn’t notice, but the beer shop owner certainly did, and told me I was the proud owner of two fake 20 boliviano banknotes. I returned to the bread seller and, to my amazement, after conducting her own investigation agreed she’d given me counterfeit money and replaced it with two new notes. Most businesses put up signs notifying customers that counterfeit banknotes would immediately be cut in half to prevent bad money from being passed on to others. I asked at a bank one day whether I could exchange counterfeit notes for real ones and the woman stared at me like I was from another planet. You’re largely on your own in Bolivia, for these sorts of things.

Chicha drinkers, Arani market. These Quecha speaking women only spoke Spanish as a second language, and not very well.

Costs

Bolivia is quite a cheap place to travel. Spending money on organized tours into the Amazon, or the salt flats, or on group hiking and mountaineering expeditions can eat up cash, but prices for food, transportation, and accommodation are low, particularly if you’re not looking for a fancy or overly comfy experience. I spent an average of $30-$35 per day for everything, which is cheap. As in Peru, if you doubled your budget you could travel very comfortably, though in some of the towns I stayed, and on some of the routes I traveled, there really weren’t any options to “upgrade”, no matter how much money you had.

The value for money in Bolivia in general across all sectors is very good. Away from the tourist areas it’s not a luxury destination by any means, but it’s not overly rough, dangerous or full of hard work. If you’ve done some of your own independent travel in non-first world places you’ll find it fairly easy and trouble free. You really need to be able to speak and read Spanish, though, to get much out of travel in most of the country.

The very Spanish flavored central plaza in sunny Tarija.

Street scene, Bermejo. I was in the far south of Bolivia in order to cross the river into Argentina.

Next up on the blog list is Ecuador, a country I hadn’t been intending to visit, but loved. I was only there for ten days, and came away with the idea there’s a lot more to see, so I’ll be back.

Stay Tuned!

Fearless Canadian explorer riding the gondola in La Paz.

* Remember! I love receiving comments, but anything you write, including when you hit “Reply” to the email notifications, is public. You know who you are…

* The photographs in this post, as well as many others, are all here.

* If you liked this story why not read some of my other blog posts? They’re all here.

* If you liked this post, why not subscribe? Sleep easy knowing you’ll never miss another story. Click on the “Follow” button, or contact me and ask to be put on the list.

Discover more from The Plain Road

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Great write up on Bolivia!

LikeLike

Food looks interesting! what was inside the empanada?

Also, those students you met, what were they interested on, what did they ask you?

Great photos!!

LikeLike

I think the empanada had ground meat in it. Savoury for sure.

The students were very shy, so it was mostly me asking them questions: what do you study in school, what do you do in town, etc. They were very polite and respectful.

LikeLike