On January 5, after five weeks in Bulgaria, I crossed into Turkey on the bus. It was my fifth visit to Turkey, a country I love returning to. It’s an excellent place to travel. People are warm and welcoming, there’s history galore, the food is excellent, transportation and accommodation are plentiful and well organized, and everything is good value. There’s just enough of a whiff of the exotic to make it intriguing, but it’s still tame, efficient and comfortable. It’s more challenging and exciting than Amsterdam, but less demanding than Ethiopia. Anyone can travel in Turkey.

To me the most interesting and adventurous parts of Turkey are the far east and southeast, but most of those areas are freezing cold and piled high with snow in the winter. This time I chose to stay in towns and cities along the Adriatic and Mediterranean coasts. It’s not quite as interesting, but the landscape is very beautiful, and the region offers history and sights & sounds that are different from the east. And, of course, it’s much warmer.

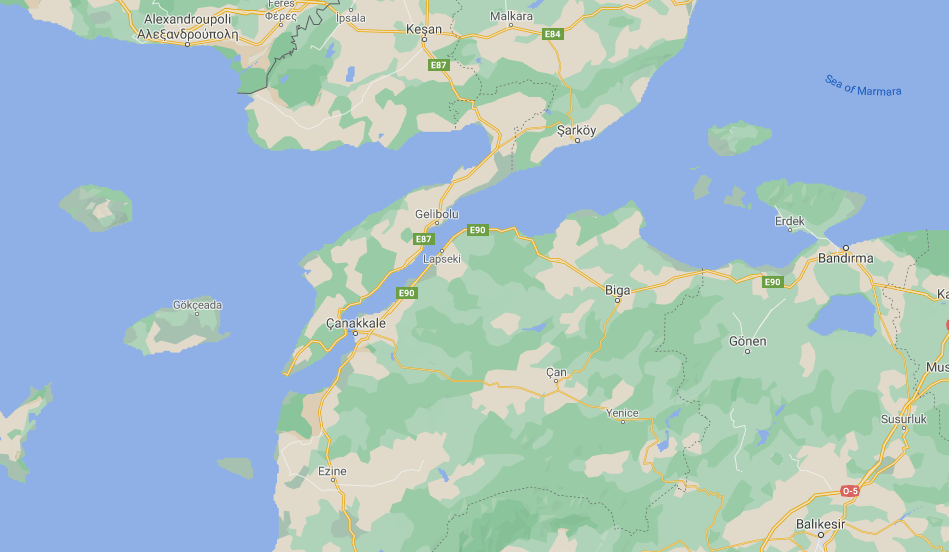

I moved in a lazy counterclockwise arch from Edirne to Antalya, sticking to the coast. I stayed in Edirne, Çanakkale, Izmir, Çeşme, Fethiye, and Antalya.

My route, from Edirne top left, to Antalya bottom right.

Generally speaking, people visit Turkey either for the wide variety of historic sites, or for the seaside resorts and sandy beaches—or both. I love historic sites; I don’t love tourist beaches. Most of the sites were still open during Covid when I was there, but the door had been slammed shut hard on the beaches and resorts. At its height in 2019, Turkey attracted around 51 million foreign tourists, ranking as the sixth-most-popular tourist destination in the world. (The most popular? France, with 89 million). Turkey is nice and hot in the summer and mild in the winter. There are sandy beaches and palm trees that attract sun seekers. Brits, Germans, Russians and Bulgarians lead the pack, but people come from everywhere.

It’s not all tourism all the time, though. Turkey isn’t loud and tacky; there are still plenty of normal towns and cities, so you can easily miss the resort stuff if you’re not bothered. A lot of the little towns, though, haven’t been able to resist the temptation and influx of money that visitors bring in, and have given over to tourism, largely domestic, sprucing up the harbors and promenades of their seaside neighborhoods. But in the off-season—or during global pandemics—the townsfolk close up the umbrellas and take in the sidewalk tables, and the towns go back to being just towns.

An empty piece of coast just outside of Çeşme.

One of the tidy and attractive harbors in Çanakkale.

On this trip I headed first to Edirne. Edirne is just 7 km (4.3 mi) from the Greek and 20 km (12 mi) from the Bulgarian borders, so it sits on a major commercial and transportation corridor for anyone or anything going in or out of Turkey by land. I arrived at the massive border station by bus from Haskovo, Bulgaria, only a little over an hour’s drive on a slick, modern motorway. At the border all passengers had to get off the bus. Our passports were stamped and our Covid PCR test certificates were inspected. A woman and her daughter hadn’t had tests in advance (a recent requirement at the time) and weren’t allowed back on the bus. The immigration guys weren’t messing around.

I’d had my test done the day before at an efficient and miraculously uncrowded clinic in the Haskovo town center. €22. The lab tech doing the swab was pleasant enough but seemed to have decided that in addition to the Covid sample she was supposed to take, she might as well mine the depths of my cerebral cortex for a tissue sample while she was at it. Man it stung! I’ve since had three more tests, all in different places, and all perfectly comfortable. A word of advice to my loyal readers: if you need a Covid PCR swab, don’t get it in Haskovo, Bulgaria.

Edirne

Edirne is a modern enough city—a large town really—and is an important government administrative center for the province and region. It was far more important, however, in older times when it was known as Adrianople. Before Sultan Mehmet II seized Constantinople in 1453 and made it the new center of his empire, Edirne was the Ottoman capital. The Ottomans built magnificent mosques, domes, minarets and administrative structures, and Adrianople was a major center of learning and Islam. When you know that, Edirne becomes a very interesting place to wander around.

The old town is attractive. In addition to the big mosques and monuments there are still a lot of wooden Ottoman merchant homes and other civic buildings, and the pedestrianized shopping streets are charming. I spent four days in Edirne, snooping around the city and walking through the farmlands to the south.

The courtyard in the main entrance to the Selimiye Mosque, Edirne.

The most important monument in the city is the Selimiye Mosque, built in 1575 for Sultan Selim II and designed by Turkey’s greatest master architect, Mimar Sinan (c. 1490–1588). Sinan is better known for designing the Suleiman Mosque in Istanbul (every visitor to Istanbul has seen it) but it’s said his real masterpiece is the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne. For what it’s worth, I agree.

It’s hard to describe how stunning the mosque is, and, for me at least, it’s impossible to do it justice in photographs. Because there were so few tourists in Turkey when I was there (and Edirne isn’t very touristy anyway) I had the entire mosque to myself on three of the four times I popped in for a visit. It was cold inside, but dead quiet, and imposing. Austere. As with all working mosques in Turkey, entry is free. You can stay as long as you like provided you don’t bother anyone. The Selimiye Mosque was added as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2011.

If you’re interested in learning more about Sinan and his mosques, this is quite good).

Interior of the Hıdır Ağa mosque, Edirne. The calligraphy reads, “Mohamad” in a mirrored design.

A woman passing the north side of the Selimiye Mosque, Edirne.

There are scores of other mosques and Ottoman buildings, scattered all over Edirne, including the Complex of Sultan Bayezid II, a hospital and medical center from 1488 which was known for its progressive treatment methods for mental disorders, which included the use of music, water sound and scents. There’s a good museum there which was open. I was the sole visitor for an entire two hours on the day I went.

Courtyard of the Selimiye Mosque.

Complex of Sultan Bayezid II, Edirne.

The ethnography museum in the Complex of Sultan Bayezid II, Edirne. I spent an excellent afternoon walking through the museum completely on my own.

All restaurants in Edirne were closed for inside dining because of Covid, but nearly all offered take-away service. Turkish food in general is excellent, and Edirne is known for its good local dishes like ciğer tava, breaded and deep-fried liver (lamb or calf). It’s served with hot dried and crunchy pepper and comes with heavy unleavened bread and a side of cacık, a cool dish of watery yogurt with chopped cucumber (like Indian raita). I tried it. It was delicious though pretty rich and heavy; two bottles of cold Efes lager eased its passage.

Fruit and veggies for sale in Edirne.

Not everything is up to date in Edirne; this fruit seller still does it the old fashioned way.

Çanakkale

It was also my first visit to Çanakkale. It’s a very pleasant smallish city (approx. 190,000) set on the Dardanelles Straights, with a beautiful long seaside promenade and a colorful, bustling harbor filled with small boats. There’s an atmospheric old town complete with a cobbled and confusing cluster of streets and lanes, lots of fish restaurants (all closed for indoor dining) and tea houses (outdoor seating only).

Çanakkale harbor.

The pleasant but average nature of Çanakkale belies its historical importance. The slim strip of ocean that makes up the Dardanelles Straight is part of a marine route that enables shipping from the Mediterranean to the Sea of Marmara, through the Bosporus at Istanbul and into the Black Sea. As such it’s always been an extremely important place, fought over by every nearby empire and his dog for as long as there have been empires (and dogs). Roman and Greek battles recount tales of fights for passage through the Hellespont between Europe and Asia—that’s the Dardanelles. Çanakkale is on the Asia side.

The Dardenelles (or the Hellespont as it was known in Greek and Roman times), an all important passage between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.

In 1915, during the First World War, the British Empire and France attempted to secure the waterway through the Dardanelles Straits and ultimately capture Constantinople (the Ottomans had sided with the Central powers during the war). With the Ottomans defeated, it was reasoned, the Suez canal would be safe, and a year-round Allied supply route could be opened through the Black Sea to warm water ports in Russia. But the Allies lost the battle.

Known as The Gallipoli Campaign, or the Dardanelles Campaign, the region is something of a pilgrimage site for Turks who still consider the campaign a great victory, and for New Zealanders and Australians who lost over 50,000 and 16,000 soldiers respectively. I didn’t visit it, but there’s a large national park nearby, the Gallipoli Peninsula Historical Site.

Leaving Europe to cross the Dardanelles Straight…

Arriving in Asia 20 minutes later.

The bus journey from Edirne involved a short ferry crossing; it was very cool seeing Europe recede in the distance as Asia approached ahead. I imagined myself a Roman general, standing at the ready at the prow of my war vessel, ready to seize land and annihilate my barbarian enemy. It was fun until I remembered I was instead a middle-aged Canadian tourist with a backpack standing beside a large bus.

Çanakkale is also the closest urban center to the ancient city of Troy. There’s a large wooden Trojan horse sitting quietly on one of the piers left over, apparently, from the 2004 movie “Troy” starring Brad Pitt. I looked at the horse a couple of times, each time for several minutes, but no one climbed out.

Farmhouse outside of Çeşme. I had an excellent walk out and around the peninsula. Most of the land on the small peninsula is high above the sea on bluffs. The day was cool but sunny and dry.

Izmir

I’d been to Izmir once before, in 1990. I wrote in my journal at the time, “I’ve arrived in the California of Turkey!” because it was hot and sunny and the long seaside promenade was lined with palm trees and beautiful people. It was still the same on this visit, though the weather was cool and rainy for four of the seven days I stayed there; it got down to 1 degree centigrade a couple of nights. The promenade is still lined with palm trees but now it’s much wider and much tidier, and there is public art and there are fancy looking coffee places.

A walking and cycling path runs the entire length of Izmir’s large harbor.

Relatively quiet and traffic calmed streets in Izmir during the weekend Covid curfew.

Izmir is quite a wealthy place, so you see a lot of Mercedes and BMW cars, and a lot of expensive looking fish restaurants. It’s the third most populous city in Turkey (after Istanbul and Ankara), and the second largest urban center on the Aegean Sea after Athens. There are 3 million people in Izmir.

I’m not crazy about the city, despite its beautiful location and (usually) sunny warm days. I find it a bit soulless, somehow. It’s very clean and there’s a European buzz about it, and I’m sure it’s an exciting place to run a business or go to university or dance at the clubs, but it didn’t really grab me. Turks seem to speak very highly of Izmir. I got the idea it has a reputation as a sort of glamorous city on the sea, expensive and a little exclusive. Maybe it’s a better place to live than visit.

The Güzelyali district of Izmir as seen from Mehmet Ali Akman Park.

It’s not entirely without interest, though. Izmir has been around a long time. In Roman times it was called Smyrna when for a while it was the most important trading port on the Mediterranean. It’s also been home to Lydians, Persians, and Greeks. Homer was born there in the 8th century BC. Alexander the Great and his army captured the city in 340 BC. But despite all that history there’s not much old stuff to see.

There’s an interesting and cavernous bazaar in the old city, called Konak, which is atmospheric and bustling, and the ruins of the Roman Agora are quite cool, standing in what looks like an abandoned field in the middle of Konak, though it was closed to visitors when I was there, due to Covid. The Ottomans took the city in 1389 and built some beautiful mosques, most of which are still standing. Several neighborhoods in the Eşrefpaşa district are jumbled together up in the hills to the south. It’s interesting up there, there are a lot of much older houses and small mosques making it feel more like a village than a city.

The hilly streets of Izmir’s Eşrefpaşa neighborhood. In contrast to the mostly modern European city, Eşrefpaşa retains a conservative village-like feel. Izmir is home to a lot of expats and foreigners, but not in this area; locals seemed very surprised to see me.

View of Izmir from up in the hills in the Eşrefpaşa neighborhood.

The view from the balcony of my Airbnb apartment in Güzelyali, Izmir.

I rented a very good Airbnb place in the Güzelyali neighborhood, in the west of Izmir, a new and well planned section of town. It reminded me of cities in southern France, with street after street of flats squeezed tightly together, and palm trees lining the ocean promenade. The food shops in Güzelyali are amazing! There are dozens and dozens of wonderful specialty shops selling dates and cheeses and wine and dried nuts & fruits and coffee and strange jams and pickles. The quality of the fresh vegetables and fruits was outstanding. I’m not much of a cook but even I managed to put together some very nice meals with the booty I found in the stores. My Turkish food vocabulary and numbers proficiency improved dramatically after Izmir.

Food shopping was a real treat and adventure in Güzelyali. The good people of Izmir eat well!

“Maybe if I wait just…a…little…longer…just…maaaaaaybe…”

Fethiye

I really liked Fethiye, despite it not being the sort of place I’d normally like. It’s essentially a Turkish Riviera tourist destination, albeit a very low key and understated one. The main thing that makes it better than your average tourist bear is that the town is not focused around a beach. There are plenty of really beautiful beaches near Fethiye, but the old part of the city with its attractive marinas and lazy seaside walkway has no beach. It does have some really great small parks with loads of benches and other public places to sit, and a long stretch of ocean filled with marinas and boats of all shapes and sizes.

There are loads of little snack and tea stalls (many, though not all, closed when I was there) and for a touristy place there are some very low key and down-to-earth restaurants and shops. Fethiye is a major boat chartering location. Things were pretty quiet when I was there but you could tell the renting of yachts and boats is big business. Charter outfits were mostly closed, but they all had signs in Turkish, English, Russian and other languages.

Even the boats were calm and relaxed in Fethiye.

Sailboats ready for rent and charter in Fethiye. In a normal year I imagine most of these would be out on the water.

Fethiye town is nestled snugly in a large but cozy natural bay, but the rest of the area is very hilly. Beautiful hills, in fact, with outstanding walking. I walked one day from Fethiye up and over the craggy hills to the deserted ancient Greek city of Kayaköy and onward to Ölüdeniz. Ölüdeniz is a typical (nasty) resort beach town, with nothing but cheap seafood places and rows of condos and ugly hotels. It was nearly completely deserted when I wandered into town, most hotels and apartments were closed up and there was nearly nowhere to eat. I almost felt sorry for it.

The walk to get there, though, was fantastic. I walked on an old rough and rocky trail that paralleled the main road. There were ruined stone farmhouses and clearings cut from the forest. I saw several local people traipsing in the forest from who knows where to who knows where. Fethiye would serve as an excellent base to explore the area. You could walk, mountain bike, hike and explore the little villages and old settlements.

One of the roads up and through the mountains from Fethiye.

The village of Belen, south of Fethiye; the ruined Greek city of Kayaköy can be seen scattered through the hills in the background.

Something left from the ruined Greek city of Kayaköy.

The Airbnb I rented for a week in Fethiye wasn’t very good. It was roomy and in a great location in a very normal, workaday part of town, but it was cold and not very clean. Fethiye is on the Mediterranean so it’s never exactly cold, even in the winter, but it wasn’t hot either. The temperature was around 18°C or 20°C by day, but down to 4°C at night. My apartment would be a wonderful place to stay in the hot summer months, as it was many times colder inside than out, but it didn’t do me any good in the winter. The lousy old air conditioning unit only mustered a feeble whisper of warmish air, and I had to wear all the clothes I had when inside.

The kitchen was poorly provisioned. There were about 25 bowls, but only one plate. Three of the forks looked as though they’d been put away without being washed (more than once). There was only one cooking pot and it was a massive soup pot like you’d find in a hospital kitchen. It was odd. When I contacted the owner to complain (gently) he immediately came over with tea towels and dishcloths (also absent), two smaller pots, an extra plate and a large mixing bowl. I would definitely visit Fethiye again, though I’d chose a different place to stay.

The resort of Ölüdeniz, seen from the hills above.

The road from Fethiye to Antalya went up and over the mountains and back down to the coast. We left Fethiye in warm, dry sunshine and 45 minutes later were in snow.

Antalya

I stayed in Antalya for three weeks, renting three different Airbnb flats from Merve, a clever entrepreneurial woman who managed them as a full time business. She was on the hunt for an additional two apartments to rent out, and had plans to expand eventually to Istanbul. All three of her apartments were great, all on upper floors of buildings with big, bright rooms and balconies. I loved Merve’s places and as a result stayed in Antalya nearly two weeks longer than I’d planned.

The sea and cliffs of Antalya.

The bright and cheerful living room of Merve’s apartment in Antalya.

Sunny warm days in my Antalya kitchen.

The view of the street from the balcony of my apartment, Merve’s Number 2 place.

Merve, my landlady extraordinaire making a repair to my apartment.

Antalya is Turkey’s biggest international sea resort, located on what’s called the Turkish Riviera. All along that stretch of Mediterranean are beach reports and towns and small cities that have turned to tourism, mostly of the fun-in-the-sun variety. Fethiye is a bit different, as I mentioned above, and Antalya is different too because it’s by far the biggest city on the coast, and most of the beach and holiday activity happens to the south of the city in a separate area called Konyaalti, leaving the city proper alone to be a normal Turkish city (population around 2.5 million in the urban area).

Konyaalti beach and district, Antalya. What’s normally packed solid with sun worshipers was gloriously empty just for me. I walked the entire length of the beach several times (it takes about 2 hours).

Antalya is very attractive and comfy. There’s a large and atmospheric old town, called Kaleiçi. There are picturesque squares, cobbled lanes, Roman ruins and higgledy-piggledy streets. There are several fantastic public gardens and spaces high above on the bluffs above the old harbor where people gather at sunset with cold beer and snacks. Some people play guitar while friends sing Turkish ballads and love songs. There are palm trees all along the waterfront areas, and lemon and orange trees dot the center of town. Antalya has an excellent tram and bus system, and it’s a decent place to walk.

I really liked Antalya. The weather was very good, a little cool in the evenings still, but lovely and warm and mostly dry in the day. It would probably be too hot in the summer. When I was there it was up to around 18°C or 20°C by day, but at the height of summer it can reach 35°C. None of the restaurants or tea stalls or bars were open for inside consumption, which was a drag because there are some really wonderful little places to eat and drink in the old city and on the bluffs above town. I spent my mornings walking and my afternoons buying the odd grocery item, and loafing around town. In the evenings I’d often go to one of the parks or gardens with a beer and a small bag of pistachio nuts.

A busy intersection in Kaleiçi, the old part of town, Antlaya.

Looking south across Kaleiçi (old town) on a bright and sunny morn.

A feline resident of Antalya. Turkey is famous for its massive stray cat population, and Antalya is no exception. This handsome specimen was found regularly just outside my apartment.

The Andızlı Cemetery in Antalya. I often visit cemeteries; it’s interesting to see the names and dates of people who’ve come before, and the grounds are usually calm and pretty. And there’s no risk of catching Covid…

Old, new, decorated and unfinished in Antalya’s Kaleici neighborhood.

Kaleiçi, Antalya.

I made a day trip to nearby Perge, an ancient city, first Greek then Roman. The town was an important ecclesiastical and trade center in the early part of the first century AD. The Apostle Paul apparently stopped there in 46 AD to do some preaching. They started uncovering the ruins only in 1946. It’s wonderfully preserved, and you can see how big the place would have been back in the day. It was nearly completely deserted when I went there on a Tuesday morning, just a Russian couple and a few Turks. I spent hours wandering around looking at the columns and marble. There’s a large theater and a hippodrome. Best of all you can get there on Antalya’s city tram system in about 45 minutes, for about two bucks.

The ancient theater in Perge, near Antalya. I had a wonderful day there, wandering through the ruins completely on my own.

Ruins of Perge.

Covid

Turkey had just started what they later called a second wave of the virus when I arrived. The federal government implements and maintains regulations and restrictions in all provinces of the country, which makes it easy to understand and follow the rules because they were mostly exactly the same everywhere. I’d intended to arrive in Turkey from Bulgaria a week sooner than I did, but just before I did the government imposed a dawn-to-dusk lock-down over the entire New Year’s period (to stop the food and party loving Turks from getting together in large, jolly groups to celebrate). It ended on January 4, so I entered on January 5. I needed to show a negative PCR test to enter (obtained, as I mentioned, under extreme discomfort in Haskovo).

Covid measures explained.

Busy street in Antalya. The city is mostly tidy and well managed, and there’s a nice mix of new, old, residential and commercial. The streets in most Turkish towns were quite safe for Covid walking.

Riding the rails in Izmir. I always felt Covid-safe on the trains and trams in Turkey. It was easy for me to avoid rush hour, so most of the time the carriages were calm and there was a lot of space.

Shops and businesses were open during the day, but restaurants and cafes could only offer take-away service. Some small tea houses put three or four tables on the street in front of their shops (no chairs) and occasionally I stumbled on a small cafe that had propped up a couple of cheeky tables deep inside the bowels of the restaurant, but for the most part they were all closed.

Gravestone maker, Antalya. Happily he didn’t seem to be particularly busy.

There was a total curfew every weekday night from 9pm until 5am the next morning, and all weekend from 9pm Friday to 5am Monday. Bakeries, pharmacies, grocery stores and other businesses deemed to be essential were open from 10am to 4pm on the weekend, but customers were supposed to go directly to the shops, do their shopping and go home. Dog walking was permitted, and I’ll bet there were a lot of Turkish dogs wondering why the hell they were suddenly getting so many walks over the weekends. (I read just the other day that they are now closing the large supermarket chains on Sundays as people were using them as places to meet and socialize!). Police meant business, and there was an army of police and soldiers (politely) asking people why they were out and where they were going. I never saw or heard any real trouble or arguments, but the police were dogged.

Catching up on the latest Covid news in Çanakkale.

Strangely, foreigners in Turkey for purposes of tourism (me) were not subject to the curfews, which meant I was allowed to walk around as much as I pleased anytime I wanted. It was a bit odd, though, as there were no tourist-only shops or restaurants, so there was nothing for me to do other than be outside. Lucky for me I like walking; it was weird at first, walking around deserted streets, but I came to really enjoy the chance to cruise around in my own little Turkish movie set while everyone else was shut up indoors.

Curfew day in Fethiye, just me and the birds.

People in Antalya were the best about following the rules, and people in Izmir the worst. By far the vast majority of people were pretty good, wearing masks and keeping something of a distance between each other, using the hand sanitizer at the doors of most of the shops. But more than a few people told me they thought the government had over-reacted. Turks are sensitive to government overreaching and authority (in my view), so I was frankly a little surprised to learn that most Turks seemed to follow the rules quite well. Like people everywhere they’ll be getting tired of being cooped up, and it’s been very hard on the small family run restaurants and little shops that have had to close or curtail their activities.

Trying to work through it all; this kebab place in Izmir was doing a booming business in take-out.

My pide being placed lovingly into the oven. Pide is a sort of Turkish flatbread pizza. They’re hot and delicious, served with grilled peppers.

I’d say Bulgaria had a slightly better handle on virus control than Turkey, but they were both quite good. Albania was the sloppiest, and Macedonia was somewhere in the middle. Anyway, I survived, and when I eventually left Istanbul towards the end of March I was rewarded with negative Covid results from both tests I took in Istanbul and when I landed back in Vancouver. I guess I have the Turks to thank in part. If everything there had been open it would’ve been very hard to resist the wonderful little eateries and pubs and baths and tea houses, so it was just as well I suppose. I’ll eat, drink and bathe twice as much the next time I’m there.

Onward to Istanbul

After my three weeks in Antalya I flew to Istanbul where I stayed for an entire month. I’m working on that blog post now, so keep your eyes peeled. In the meantime,

Stay Tuned!

Sunset in Antalya from one of the many plazas around town.

* Remember! I love receiving comments, but anything you write, including when you hit “Reply” to the email notifications, is public. You know who you are…

* If you liked this story why not read some of my other blog posts? They’re all here. Photos are collected here.

Discover more from The Plain Road

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

An excellent read and beautifully illustrated as usual. It sounds like an area that it is well worth visiting and I have put it on my list.

It also sounds like an experience visiting during COVID.

It almost seems that missing those wonderful little eateries, pubs, baths, and tea houses was worth it for those unique weekends of solitude.

LikeLike

Thanks, Trainstobeyond, I appreciate the feedback. You’re right: it was ALMOST worth missing the food and baths for the quiet weekends, but I would far rather put up with crowds for a chance to eat inside at a sit-down restaurant! Definitely worthwhile traveling during Covid, in general, for the experience.

LikeLike

Love reading about your journeys and your photos are fantastic. Really get the flavor of every country.

LikeLike