Bulgaria as a travel destination was never really on my list. Wait, actually that’s not true: it wasn’t on my main list, it was on a secondary or tertiary list, along with Romania, Ukraine, Russia and Belarus. I hadn’t thought specifically about Bulgaria in recent years but finding myself in the general vicinity this winter, I decided to go. I assumed, mainly because of its location, it would be interesting and offer a rich and storied culture, historic treasures and a proud people. It was handy: Bulgaria sits between Macedonia (where I was) and Turkey (where I was going). The most compelling reason to go, though, was that Bulgaria was actually open, no small thing in these days of pandemic travel. It was open and they weren’t asking for any tests or quarantine, so Bulgaria moved to the top of my A list.

I spent five weeks there, arriving on November 29 overland from Macedonia. I stayed ten days in the capital, Sofia, then rented a car for a week and explored the Black Sea region and the southeast, near the borders with Greece and Turkey. Then I spent a little over two weeks in Plovdiv, Bulgaria’s second city. Three cold nights in the medieval city of Veliko Tarnovo, a few other nights here and there, and that was the five weeks. After Bulgaria I moved on to Turkey where I stayed for nearly three months (blog post coming soon!).

Bulgaria sits in the southeast corner of the Balkan peninsula. Sofia is in west central, Plovdiv is in the south central.

Overall I really liked Bulgaria and could have stayed longer. Five weeks was by far the longest time I’d ever spent in a Slavic country (very brief visits to Poland and Ukraine the only other times) so it was interesting and worthwhile learning something about life there, and seeing a region I knew really very little about. Bulgaria has in recent years become quite touristy because it’s a bargain compared with more northern European places, and there’s a lot to see what with its monasteries, charming cities, Black Sea coast and great outdoor opportunities. None of that mattered to me, though. It was winter and a second wave of the pandemic was sweeping through Europe so the resorts were closed and the tourists were long gone.

The town of Veliko Tornovo seen from Tsarevets fortress during a brief pause in the rain.

Sveta Petka church, Plovdiv.

At the top of the list of positives is Bulgaria’s geography and scenery. It’s beautiful, even—and often especially— in the dead of winter. The Balkan mountains run smack dab right through the middle of the country. The Rila, Pirin and Rhodope are the main groups, and some of their peaks reach 2,900 meters (9,500 feet). Bulgaria is very rural, with plenty of quaint little village farms and oldy-worldy towns. Bulgaria’s entry to the European Union has ensured much greener economic policies. They still have bad air pollution in a few places from coal-fired plants, but generally the country now boasts clean rivers and well-managed woodlands.

Typical slate roof seen on churches, houses and other buildings in the Rhodope mountains (this one near Smolyan).

It’s obvious to anyone on even the shortest visit to Bulgaria that Bulgarians love the outdoors. Cities like Plovdiv and Sofia are spoiled for beautiful parks and gardens, and there are well signed, well organized and well maintained hiking, walking and camping areas everywhere.

Much of the country is rural, and very pretty. Every town has a central pedestrian area lined with benches and (in normal times, and outside of winter) cafe and bar tables. Whoever won the contract to supply Bulgarian towns with park benches must be on the Forbes 500 list because I’ve never seen so many places to sit outdoors. And the density; I don’t know if there’s a universal standard for bench spacing, but if there is Bulgaria ignores it. Pedestrian streets and parks are lined with literally hundreds of park benches spaced no more than a meter or two apart; and despite it being winter when I was there, any hint of a bit of sun or warmth sent hardy souls outside to a bench with coffee, cans of beer and sandwiches. Every place was like that: head to the center of town and sure enough, there would be a (sometimes very large) area of closed-off and pedestrianized streets, filthy with benches.

Plenty of pedestrian friendly walkways and benches in Yambol.

It’s not all beer and skittles though; there are some God awful looking towns in Bulgaria, with their exhausted old stained communist buildings and sagging factories. But even in those towns there were pleasant parks and comfortable, well-used pedestrian zones for the locals to gather (with lots of benches) and always a couple of charming little farmhouses and pretty countryside scenery.

Not all towns in Bulgaria are pretty. I like to think—hope— this place looks a lot better in the summer.

Sofia

Sofia was a happy surprise. I really liked the city and would love to visit again. It has an interesting and inviting blend of what I thought looked central European and what looked a little more like Russia or Ukraine. You could be dropped into much of Sofia and you’d swear you were in Vienna, or Paris, with the grand boulevards, gardens and pretty little squares. But then turn a corner and you’ll find yourself standing in the courtyard of a Russian orthodox church, or in front of a long stretch of concrete Stalinist apartment blocks. Most of the city looks modern and up to date, but there are still plenty of corners that are tatty and old and Soviet, perhaps with a bit of garbage dribbled on the street like a scene from an old spy movie set in East Berlin in the rain.

Sveti Nikolay Mirlikiiski Russian Orthodox Church on a cold and snowy morning.

Central Sofia, after some rain.

Greater Sofia has a population of somewhere around 1.5 million, but it feels somehow much larger. It’s the largest city in the country, by far, (Plovdiv is the second largest city with just 338,000), and the nation’s commercial, political, artistic and industrial hub, so it has correspondingly big britches, and feels that way.

Sofia is an excellent city for walking. The roads and sidewalks are well maintained and there are a lot of pedestrian-only roads. People walk a lot. There are several enormous parks: West Park, South Park, and Central Park are the main ones, and despite their unimaginative names they’re wonderful green spaces, with stands of forest, walking trails, fountains, flower gardens, and places to sit and eat or drink. There’s also Borisova Garden, Vartopo Park, Geo Milev park, a beautiful botanical garden and an enormous central cemetery that’s beautifully wooded and pastoral and filled with the most interesting tombstones and grave markers.

Walking through Sofia’s West Park. Sofia has a half dozen huge parks, as well as countless gardens and green spaces.

I made a point of walking at least a little through all of them. West Park is the most wild, much of it covered in thick deciduous forest and rough, muddy walking trails. Sofia also has its very own mountain, Mount Vitosha, one of the symbols of the city and the closest site for hiking and skiing. It’s just on the outskirts, and easily reached by city bus. Vitosha isn’t just a sort of glorified urban park, it’s a proper mountain with proper wilderness, right on Sofia’s doorstep; it’s a fantastic natural resource.

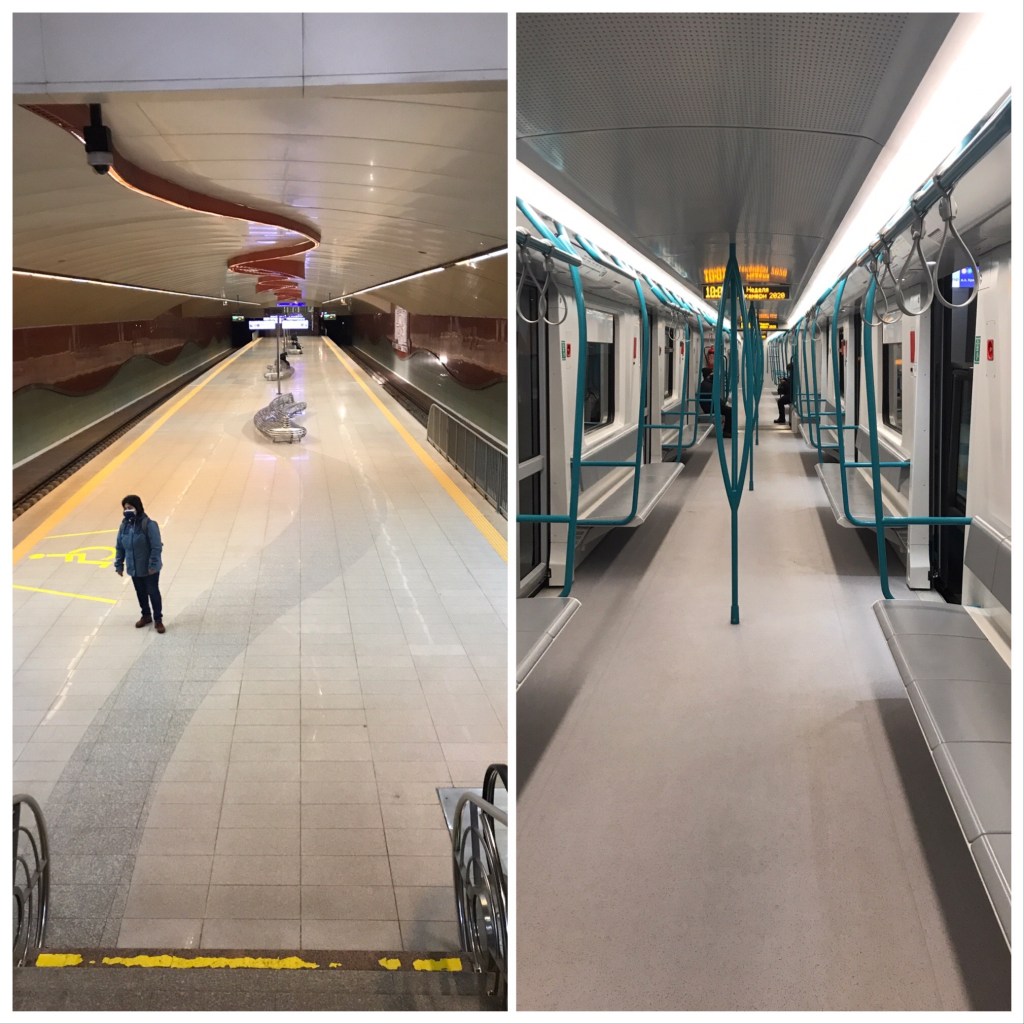

A quiet day on the Sofia metro. Even during rush hour the metro was never as busy as the trams and buses. It was odd, because the metro is excellent: efficient, clean, fast and cheap.

Sofia was cold when I was there. In fact it snowed the night I arrived and I awoke the next morning to six inches of pretty powder on the ground. Like all cities covered with new fallen snow, Sofia looked impossibly charming and wonderful for about four hours until it warmed slightly and the snow turned brown, then to slush. Bulgarian winters are cold, but houses and buildings are equipped with good radiated heat and wood burning stoves. Anticipating colder climes to come I’d bought a big puffy winter jacket at a used clothing market in Albania so I had no trouble keeping warm in Bulgaria, inside or out.

Sofia looked beautiful in the new snow, until it all melted and turned brown.

I can tell you one thing: Sofia must be fantastic in the summer, and when there’s no annoying virus keeping things closed. There are so many parks and gardens and cozy little plazas with fountains and tree-lined cobbled streets filled with cafes and bars; I kept thinking how pleasant it would be to be able to sit under a warm summer sun at a sidewalk cafe and enjoy a beer or a coffee. Next time.

Waiting for the tram. Sofia has an excellent public transportation system with trams, metro, buses and trolleybuses. I liked riding the trams best.

Road Trip

I rented a car for seven days from local outfit Vivorent (€105 for the week – cheap!). It came with unlimited mileage and a peppy engine so I was able to cover a lot of ground. I really enjoyed the freedom. I picked up the car in Plovdiv and did a clockwise loop, driving east to the Black Sea, then south onto small coastal roads until I hit the Turkish border. Then I turned west and explored the border villages until the road turned up into the Rhodope mountains, then down again back to the relative flats of Plovdiv.

I learned very quickly there are three main types of roads in Bulgaria: There are the motorways/highways, the secondary but still important main roads, and then everything else. The motorways are excellent, essentially the same as those you find in the U.K. or Germany or the U.S. Once on those you can fly. Bulgaria is not very large, and the speed limit on the motorways is 140 kph (ignored by everyone) so the miles fall away quickly.

A typical rural road in out-of-the-way southeast Bulgaria.

Smaller roads in countries where populations have been settled for a long time, like Bulgaria, are there because they’ve always been there, first as trails, later as pathways for cattle and carts, then eventually as roads for movement. There are a lot of twists and turns and there are a lot of buildings and houses and driveways and farm vehicles and delivery vans and driveways all along the way. The speed limit on main secondary roads in Bulgaria is 90 kph and I was amazed and astonished to find people—lots of them—exceeding the speed limit, like death-loving maniacs. Bulgarians drive like loons, rain or shine, straight or twisty, smooth or rough, and in any sort of vehicle, it seems to make little difference. I took it easy and almost always moved over to let others blow past and consequently am still alive to write about it.

A typical farming village near the border with Greece, southeast Bulgaria.

I was stopped several times by very bored policemen who set-up on the side of the road on the outskirts of towns and stop people who fail to illuminate their daytime running lights, or disobey some other rule. I learned to say, “Hello!” and “How are you?” and “I am from Canada,” in Bulgarian, which they seemed to appreciate. I was asked for my passport a couple of times, but the policemen were never aggressive or pushy.

The town of Smolyan in the Rhodope mountains.

I found the most interesting area of the country to be the region near the border with Turkey, tucked quietly in among rolling, rocky farmland filled with sheep and cattle. The border fence is mostly hidden from the road, though every once in a while you come across a guard tower or metal rails. My interest of the border area was primarily because of what I’d read about Bulgaria’s history. I can’t tell, having been there for such a short time, and not being able to really have conversations with Bulgarians, but I got the idea Bulgarians are quite nationalistic and very proud of their country.

Bulgaria is the oldest country in Europe that hasn’t changed its name since it was first established. Sofia was inhabited 7,000 years ago and established in 681 AD which makes it the second oldest city in Europe. There have been a number of large and powerful Bulgarian empires. Bulgaria is a member of the E.U., and are working hard to join the Eurozone monetary union. They have much to be proud about, and they really consider themselves to be European. I got the idea that they’re often overlooked within Europe; tourists think of Bulgaria as part of the Balkans and not a part of “real” Europe, which (I think) makes them nationalistic and sensitive to their image and their Bulgarian-ness.

The small town of Mezek, as seen from the medieval fortress south of town. The Mezek region makes some of Bulgaria’s best wines.

Bulgaria was under Ottoman Turkish rule for more than five hundred years, something I think they’re trying hard to forget. Bulgarians like to be Bulgarian, and I read that there’s currently a re-emergence of hostile attitudes towards ethnic Turks and an increase of anti-Turkish outbursts. Several fringe parties—some of them still represented in the Bulgarian parliament—keep agitating against Turkish Bulgarians and are fighting against their rights as a minority. There are real life examples. In 1989 the communist regime in Bulgaria started to assimilate the Turkish minority by force. Turks were no longer allowed to speak Turkish in public and were issued identity cards with new names that were “more Bulgarian”. Thousands fled across the border into Turkey.

Church of Sveti Sedmochislenitsi, central Sofia.

The “Devil’s Bridge” crossing the Arda river in the beautiful Rhodope mountains, one of many Ottoman bridges in Bulgaria and the Balkans.

The small villages near the Turkish border looked different than the villages farther north, even just a little farther north. It’s tough to put my finger on it, but stopping in those little towns to buy a snack or get gas gave me a different feeling for the country; it just seemed different. I didn’t see locals walking around wearing “I’m an ethnic Turk living in Bulgaria” t-shirts, but there’s some sort of hint in the air, the way the people interacted with me and each other, the layout of the towns. I thought maybe the people were a little wary of me, or suspicious. It could have been because I look more like a Bulgarian Slav and less like a Turk, and there’s some distrust there, but it could also just have been that I was a stranger to their little towns. I stopped the car a lot to walk through the villages.

The most interesting few days of my road trip were the ones exploring near the border with Turkey.

Waiting for the sheep to cross the road, near Orintsi.

Plovdiv

After my road trip I spent two weeks in Plovdiv, including Christmas and New Year. Many countries in Eastern Europe celebrate Christmas on January 7th as most Orthodox Churches use the old Julian Calendar, but the Bulgarian Orthodox Church uses the Gregorian calendar, so Christmas is on the 25th. It was very quiet for me; I celebrated back in my apartment with pasta in a zesty tomato and pepper ragu, a bottle of lager beer and a documentary on the television about Christopher Columbus.

Plovdiv is Bulgaria’s “second” city. It’s far more charming and quaint than Sofia and in fact was the European capital of culture in 2019. Plovdiv was an important Roman settlement in the first century AD, but before that it was an important Thracian city, and before that a location for a variety of Neolithic settlements. Alexander the Great was there for a time, as well as the Persians and of course the Ottomans, so there’s plenty of history. Plovdiv is among the few cities in the world with not one but two ancient theatres, one of which is extremely well preserved and was miraculously open to visitors when I was there (I guess because it’s outdoors). There are remains of medieval walls and towers, Ottoman baths and mosques, a well-preserved old quarter from the Bulgarian National Revival period with beautiful houses, churches and narrow paved streets. And it was largely empty of tourists.

Historic Plovdiv is very laid back and pedestrian friendly.

Ice skating in Plovdiv main square.

Roman theatre in Plovdiv, built in the 1st century CE during the reign of Emperor Domitian when the city was known as Philipoppolis.

I spent my two weeks walking far and wide. Plovdiv doesn’t have as many large parks and gardens as Sofia, but it’s still an excellent city for exploring on foot, and is far more compact. The weather was slightly warmer and drier than when I was in Sofia. There are six hills in Plovdiv, each with its own name (Hill of the Youth, Hill of the Liberator, and so on). A good day’s walk would include a brisk trip through the old city, a romp up and down several of the hills, a traverse through a few parks and gardens and a last couple of kilometers on the path alongside the Maritsa River.

Plovdiv seen from Danov Hill on a lovely warm and sunny New Year’s Day, 2021.

Then it would be time to sit and drink a coffee from a vending machine. There are millions of them all over the country, even in the tiniest towns, and they all dispense surprisingly good, scalding hot coffee, tea, or hot chocolate. Plovdiv and especially Sofia have a decent (and growing) hip coffee scene, but people seem to love their machine coffee, and so I learned to as well.

I memorized the Cyrillic words for espresso, double espresso, long espresso, cream, milk, sugar, hot chocolate, and tea. I could barely say Please and Thank you in Bulgarian, but I was fluent in coffee vending machine nomenclature by the time I left.

Vending machine coffee! Not all machines listed options in English so I learned most of the coffee related words in Bulgarian.

Hill of the Youth, Plovdiv.

Covid-19

All this discovery, exploration and coffee drinking happened beneath the backdrop of a raging, global pandemic. I was well aware of the virus, of course, and I wore my mask and washed my hands and stayed away from people where I could and then just carried on and tried not to worry too much about it. Covid rules in Bulgaria centered on business and events restrictions, and mask wearing. All shops were permitted to open but with limits on the number of people allowed in at any one time. Everyone was quite strict about it. It was common to see a line of a half dozen people standing patiently outside the door of a store, waiting their turn to enter. Except, for some reason, supermarkets, which always seemed to be packed and disorderly. People in smaller shops were courteous and aware, but not so the crowds in the larger supermarket chains (Billa, CBA, Fantastico, and T-Market the main ones) who went about their business like it was the last chance they’d ever have to buy milk and bread. It was odd.

Things are calm and orderly on the streets of Stara Zagora.

Mask wearing was mandatory inside any building or shop, and outdoors when you couldn’t stay at least two meters distant from other people. Bulgarians were very good about indoor mask wearing, though there appeared to be more flexibility when outdoors. Many folks wandered around with masks down around their chins, then yanked them as they entered a shop (which is the opposite of Albania where locals removed their masks when they went indoors, better to greet your neighbor and kiss his cheeks). There were restrictions on the number of people who could gather in groups outdoors, though I’m not sure it was enforced. I saw fairly large groups (15 or so) of mainly young people all chatting together, drinking coffee and smoothies as they walked through the streets and sat together on park benches.

Keeping your distance is easy in a Sofia park.

Food & Drink

All bars and restaurants were closed entirely to indoor and outdoor seating, leaving takeaway and delivery as the only option. Bulgarian winter food features a lot of hardy soups and stews and doesn’t lend itself well to being taken away, so a lot of places just closed entirely, which left cooking for yourself, or eating food that’s easier to take on the go, though I did take home a few Bulgarian meals now and then.

Bulgarian take-away: stew, stuffed meatloaf and stuffed red pepper. It was good!

The doner is fully established in Bulgaria (introduced to the Balkans by the Ottoman Turks), and there are takeaway doner places everywhere. Pizza runs a close second. Usually doner meat is chicken, and is served with lettuce and tomato, pickles, french fries (wrapped inside the doner) and several resounding dollops of mayonnaise, ketchup or other sauce, all wrapped for takeaway. There were Chinese restaurants in Sofia and Plovdiv (some very large), so Chinese take-away was also an option. You won’t see a write up in the gourmet food magazines about Chinese food in Bulgaria anytime soon, but it’s filling and reasonably tasty, if not exactly authentic. Produce and dried fruits and nuts were good, meat quality was high, and supermarkets had nearly everything you’d find at home, mostly much cheaper.

Waiting to buy fish. Public and street markets were a little less Covid-friendly, but still not too bad…

There is always a nearby bench to sit on in Bulgaria, so a take-away doner and a bottle of beer or juice makes for a cheap and filling lunch on the go. I had my own kitchen by staying in Airbnb places so I cooked a lot too, mainly pasta, soups, and charcuterie style meals. Every town has a deli where you can buy cheeses and meats, different sorts of pickles and stuffed peppers. Sofia had a handful of vegetarian or vegan places, but on the whole I’d say the concept of vegetarianism hasn’t reached most of rural Bulgaria and isn’t likely to get there anytime soon.

On the outskirts of Veliko Tarnovo on a cold, rainy day walk.

Bulgaria has good beer. Most of the popular brands are of the fizzy European lager/pilsner style but they’re generally quite good. Some of the national breweries also make a darker beer, which can be tasty. There’s a decent craft beer scene in Sofia and Plovdiv (available in cans and bottles only, the bars were all closed so I never had a chance to try any draft), with a lot of pale ales, stouts and browns but also some sours and session ales. Many of the delis and supermarkets sell a good variety of beer imported from the Czech Republic, Germany, Belgium, the U.K. and elsewhere in Europe, and I found a couple of “Beers from Around the World” places in both cities, so my whistle was well whetted the entire time. Bulgarian wine is good too, and fantastically cheap.

Now we’re talking my language! Bulgarians like beer and the selection is good.

I stayed in Airbnb flats in Sofia and Plovdiv, and in hotels in the other towns when I was on my road trip. The pandemic ensured there was plenty of available accommodation, so I had excellent digs in all places. My Sofia flat was one of two apartments within a modern mid-range hotel so it was slightly institutional but was new, had excellent hot water & heating, strong wifi and good quality beds and blankets. My place in Plovdiv was one of two small studio apartments that had been built onto the side of the house owned by a big guy named Stoiko. My unit had a small kitchen, spotless bathroom and shower, firm mattress and these amazing double glazed windows that blocked out all sound. Both places had washing machines. I could do my own cooking and laundry, I had comfortable places to sit and read or watch TV in the evening, and not having to rely daily on restaurants for food and drink eliminated a potential Covid risk (though I sorely missed table meals and pubs!).

A dock at the rowing tank in Loven Park, Plovdiv, a favourite place to walk for me and the locals: one lap around the tank is about 10km

Plovdiv street, late afternoon.

The hotels I stayed in on my road trip (and the few other nights I was moving from Sofia to Plovdiv) were mostly of the large ex-Soviet era concrete type. They were unfailingly good value. Rooms were sparse and pragmatic but always clean and orderly. Towels and sheets were starched. Hot water radiators kept the rooms warm and the bathrooms provided no-nonsense soap and toilet paper. As part of Covid prevention hotel staff were supposed to check the temperature of all arriving guests, but it only happened to me once, in Stara Zagora (I tested normal).

Typical small town street in southeast Bulgaria, this one somewhere near Radovets.

Plenty of space here to spread out; Plovdiv.

Bulgarians

On the whole I’d have to say Bulgarians are not overly friendly towards people they don’t know. They’re not unfriendly exactly, and I found them to be generally courteous and helpful, and very calm and relaxed, but not warm or welcoming. I’d heard the same about other Slavic countries. Bulgarians don’t feel it necessary to be artificially effusive or polite with people they don’t know. In groups they seem very jovial. Families and friends together in the park, for instance, were very cheerful and warm, sharing hugs and kisses. But in shops and at the train station or hotel reception desk dour, unsmiling faces were the order of the day.

The big caveat, of course, is that I was there in the middle of a rampaging pandemic when most small non-essential businesses were shuttered, bars and restaurants were closed and the future was unclear. Those sorts of conditions don’t put a spring in anyone’s step, so a bit of curtness can be excused; but based on things I’d heard and read I think the way I saw them is mostly the way they are, even in times when killer pandemics aren’t prowling their streets. I never had any problems whatever and got along well with the locals, but it’s definitely not a warm & friendly vibe you get.

The Aleksandar Nevski Cathedral, one of Sofia’s main landmarks.

I learned a dozen phrases in Bulgarian. Their grammar is complicated and fussy, so I limited my fluency to “Hello”, “How are you?” “Where is…?”, “A double espresso with cream, please,” and “Goodbye”. I learned to read Cyrillic. Learning the letters was easy and fun, and by the end of my time in Bulgaria I could read absolutely everything. I had no idea what anything meant, but I could read it.

Communicating in English wasn’t too problematic. It’s not exactly widely spoken, but I found most people in shops and at the takeaway places could speak a bit. Younger people were a surer bet than older people, and some of them (the younger people) actually spoke excellent English. Most road signs were in both Cyrillic and Latin alphabets, though the road map I bought was in Cyrillic only, so I was able to sharpen my reading skills while on the road.

Bulgarian mobile phone carriers offer cheap SIM cards and data & voice packages and coverage is excellent, so I was well connected.

Bulgarian Revival houses in Plovdiv old town.

Travel the world, but stay away from the people you meet there.

Because of Covid I had very little personal interaction or even contact with Bulgarians. It was hard to meet people. My usual arena of choice for deep, meaningful, intimate and lasting contact with locals in any country is the pub. Even the shyest and most polite local becomes interested in you when he’s drinking. Language skills improve dramatically and that’s when you learn a lot. That option wasn’t available to me in Bulgaria. It was usually too cold for outdoor drinking and chatting, and as a tourist I didn’t belong to any clubs or attend any classes, or have a bubble or any other reason to contact people so it was tough learning more about the country directly from the people who live there.

Other than when I visited North Korea (see here), Bulgaria is the country where I’ve had the least amount of daily interaction with locals. It’s mostly the pandemic to blame, of course, but Bulgarians are a tough nut to crack. I was in Turkey for nearly three months just after Bulgaria; there was plenty of Covid there too but the Turks were very polite and friendly and eager to chat. As for the Albanians: “Covid? What Covid? Come here and sit with me and have a coffee and meet all my friends!” So it’s not just Covid that makes it hard to meet Bulgarians.

That doesn’t mean I didn’t like Bulgaria, I really did. The country is very beautiful, Sofia and Plovdiv were great, and the villages and towns in the mountains and along the Greek and Turkish borders are really intriguing. Things are orderly and calm, and the country is developed and efficient.

Nothing fancy, but Bulgarian towns are usually neat and tidy and calm.

Bulgaria is a good value destination, especially if you keep things simple. It was fairly cheap for me. Restaurants and bars being closed definitely cut costs. I spent little on transportation as I mostly walked everywhere and didn’t travel much between towns and cities. The few trains I took were comfortable, on-time and cheap. In normal, non-pandemic days you’d spend more I’m sure, as competition for rooms would be greater, restaurants and bars and cafes would be open and inviting, and there would be more to do in museums (all closed), shops (restricted), and at general tourist attractions. But even still, compared with much of western Europe, and considering the quality and variety on offer, Bulgaria offers excellent value. Sofia and Plovdiv are both great places for a city break (in summer when there’s no pandemic).

The Bachkovo Monastery near Asenovgrad, one of Bulgaria’s many beautiful working monasteries.

I’d like to spend more time in Sofia, in summer and when there’s no pandemic (have I mentioned that before?); I liked Sofia and Plovdiv both very much, but I think I prefer Sofia. It’s a little more raw and unfinished, and more anonymous like a big city; there are more nooks and crannies to explore. I could easily see spending a couple of weeks there “in between” trips, maybe when I want to stay in Europe for a little longer but don’t want the expense or crowds of places farther north.

Bulgaria whetted my appetite for Romania and Ukraine, but in the meantime we’re off to Turkey next, so…

Stay tuned!

* Remember! I love receiving comments, but anything you write, including when you hit “Reply” to the email notifications, is public. You know who you are…

* If you liked this story why not read some of my other blog posts? They’re all here. Photos are collected here.

Fearless Canadian explorer braving harsh and dangerous conditions to get the perfect shot.

Discover more from The Plain Road

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You are making the best of this Covid lockdown. Some fabulous adventures. Its hard to choose where I’d go first but Sophia looks intriguing as a walkable city. Keep on trekking!

LikeLike

All very interesting and, as usual, with excellent photographs.

I only made it to Sofia once on a business trip in the 90s.

Reading this makes me want to go back, although in summer and after COVID, of course !

LikeLike

Very enjoyable read. Really detailed and informative.

It’s given me a bit of resolve to get out of the U.K. as soon as we’re allowed to next month.

LikeLike