Before you say anything, yes, I am aware of the global pandemic and that most people are currently staying home. I can tell because in the past nearly two months on the road I’ve seen a grand total of – maybe – two tourists. Perhaps they know something I don’t. Hmmm. Regardless, and for reasons that are entirely selfish, I determined in the summer that because the pandemic is a global pandemic, it meant that one place on the planet is as good or as bad as the next. With that sound logic safely tucked away off I went in October to the Balkans.

I hadn’t planned to go to the Balkans. When coronavirus came to town I was in Colombia on what was supposed to be a five-month trip through South America. Everything started shutting down, including the airlines, so I was unceremoniously sent packing back to Vancouver in late March. I was going to spend most of this fall and winter in Taiwan, Thailand and Japan (read: now) but it was obvious fairly early on that that wasn’t going to happen either.

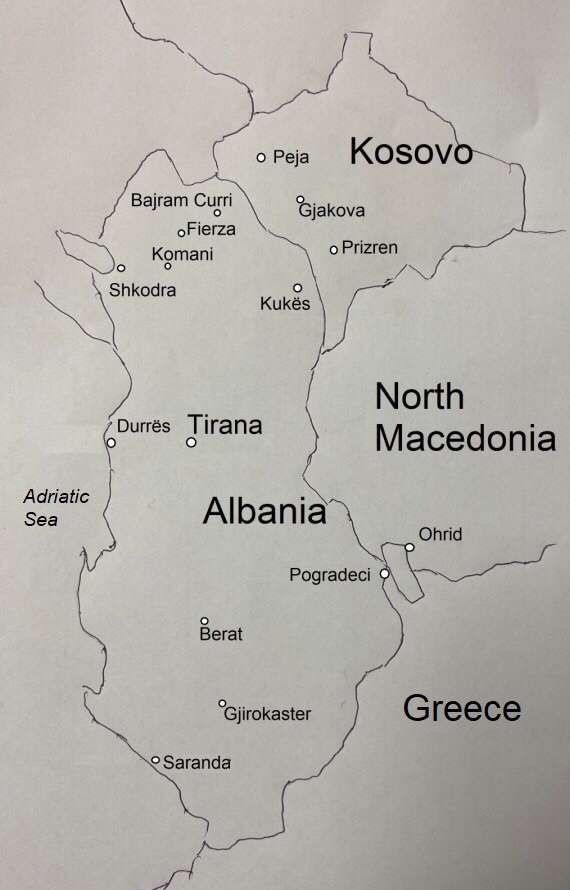

I cast around looking for somewhere to go and learned that the Balkans were doing pretty well, having limited their infection numbers during the first wave through strict and early lockdowns. As a result they were some of the first countries to reopen, and when I left Vancouver in October Albania, Kosovo, Macedonia, Greece, Montenegro, Bulgaria and Turkey were all open for Canadian travelers, with no restrictions. I went to Albania to start my adventure.

I’m still in the Balkans (in Bulgaria now as I write this), healthy and happy, though the European “second wave” has reached us too and the picture is not as rosy as it was. As far as I know I’m still Covid free, and if it stays that way I’ll keep at it until February or March, or until someone tells me otherwise and sends me home (sorry mom, that doesn’t include you).

Albania

Despite having had no plans to visit I actually had been interested in Albania since the late ’80s when the Berlin Wall came down and the Soviet Union began to fall apart. Albania hung on the longest of all the eastern block countries, not abandoning communism and opening to the outside world until 1991. Albania was one of the most isolated and locked-down of all the countries behind the iron curtain, and its ride out of a dark dictatorship into a daylight Europe took a long time. I was curious to see what the place was like now.

Albania is not very populated, with only 2.8 million people, nearly half of them in the capital Tirana which is the only city in Albania listed as having a population over 250,000 (it’s home to 418,000). Seven other cities are listed as having populations between 50,000 and 250,000 but the largest of those, Vlorë, has only 79,000; everything else is just plain little. That, and the fact that the country hides so much of its population in the valleys and mountain passes creates a real feeling of calm, space and quiet.

Outside of the larger cities there are few people, and in many places there are few signs of any people. I walked a lot in the countryside, and once out of town I’d typically wander for hours without seeing more than a few souls. There were houses and farms and the occasional shop, but not many people in any of them. And sometimes not many houses, farms or shops, either.

Scenery is a real highlight of a trip to Albania. It’s very beautiful with its rugged mountains, rolling farmland, long stretches of Adriatic and Ionian coast and pretty, historical towns. People are very warm and welcoming but not overpowering; they look after you, and they look out for you, but they don’t interfere. The country is extremely safe. I never felt threatened or nervous or even wary, anywhere. I’m sure I was never overcharged or cheated; in fact after a few days in the country when I bought anything I just held out my hand, full of money, and invited the merchant to take the correct amount. There aren’t many counties where I’d do that.

I’m sure Albania has its share of problems and warts like anywhere else but for the foreign traveler it’s a very pleasant country; there’s no hassle, no drama, and there are no big problems, other than a deadly plague lurking in the shadows, but that’s not Albania’s fault.

I started in Tirana then went east to the Tropoja region, full of craggy mountains, rivers and high forests. It’s the poorest region of the country, but one of the most visited because of the wealth of alpine hiking and camping. A highlight is the boat journey across Lake Koman, through tight inlets and deep ravines that at times look like fijords, or something from Lord of the Rings.

I spent time in the middle/south of the country in the old Ottoman towns of Fier, Gjirokaster, and Berat. The center of Albania sits at a fairly high altitude turning the late autumn days into chilly evenings.

I visited two cities on the Adriatic, Durrës and Saranda. Durrës was an important Roman city in the 8th century (called Dyrrachium) and still retains some of its class and elegance though has largely given way to beachside development, casinos and seasonal condos. More so in Saranda, which, despite its glorious setting in a beautiful warm bay with torquoise waters, is a tacky, temporary place. It was quite pleasant when I stayed there for a few days because there were no tourists and it was lovely and warm, and the walking was excellent, but you wouldn’t want to be there at the height of a regular summer season.

What’s Unique About Albania?

Leaving their communist past behind so late is not the only thing Albania stands out for. The origins of the Albanians themselves, I learned, is still something of a matter of debate. An Illyrian tribe referred to as the “Albanoi” is mentioned in Greek and Roman records, but sparsely, and no one knows where the word came from. The same root, “alban”, has stuck in English, German and many other languages as a way of identifying the people and place, but the Albanians themselves refer to their country in Albanian as “Shqiperia”, an almost unpronounceable tongue twister that doesn’t sound like “Albania” no matter how hard you try. The gap suggests the Greeks and Romans who mentioned the Albanoi had little or no actual connection to the people or region.

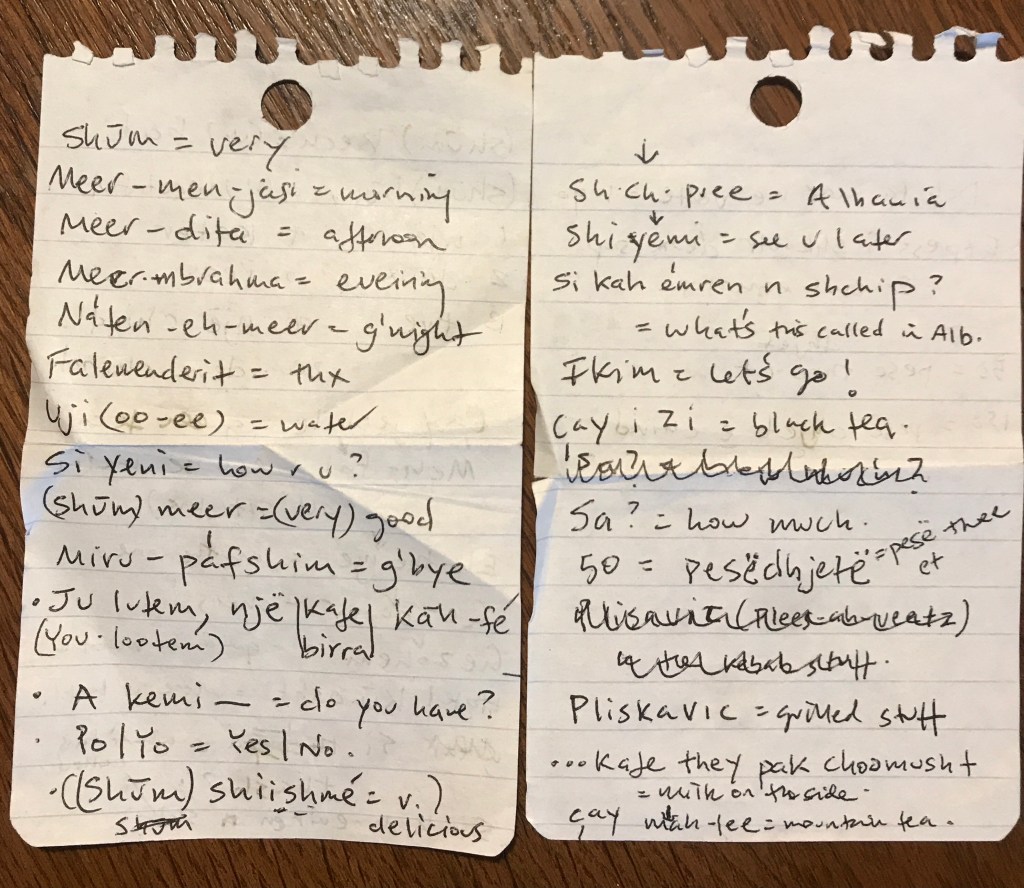

The Albanian language is unusual too, with its very own lonely position way out on a branch of the Indian-European language tree, unrelated to most anything, its origins too unknown. It has a bear of a grammar, but I managed to memorize a dozen simple phrases, which was helpful. English really isn’t widely spoken at all, though to be fair I didn’t come in contact with anyone in tourist areas where you’d normally find the English speakers.

Politically too Albania went on a road of its own during the days after WW2, staying for the most part unaligned. Under the communist dictatorship of Enver Hoxha (1908-1985) Albania pursued a policy of independence and isolation. Hoxha disagreed with the Yugoslav communists and broke a fragile alliance with them in 1948 to jump into bed with the Soviet Union. He then broke off relations with the Soviets in 1956 and buddied up to the Chinese communists under Mao. He eventually tired of them and by the beginning of the ’60s Albania closed its doors and raised the drawbridge and went it alone.

Hoxha started off well. When he came to power in 1943 he inherited a poor, illiterate, undeveloped and battered country, soon to be battered even harder by the devastation of WW2, but he made enormous gains very quickly. He built Albania’s first railway line, raised the adult literacy rate from 5% to 98%, electrified the entire country, eradicated disease through national innoculation programs and developed the farm infrastructure to the point where Albania became agriculturally self-sufficient. He advanced women’s rights dramatically. He rebuilt the healthcare system and paid for roads.

As often happens with these sorts of people in those days, when he wasn’t improving the infrastructure he managed to find time to initiate a long spell of political repression, build massive forced labor camps, kill dissidents, stifle the media and deploy an enormous secret service that spied on everyone.

In 1976 Albania became the first country in the world to be officially aetheist, making any religious practice illegal and punishable by prison sentence. Hoxha was paranoid and worried about invasion. To this day you can find concrete bunkers everywhere; apparently he built more than 173,000 of them, scattered all across the country. Most of the ones I saw (and I saw dozens and dozens) are in farmers’ fields and on the banks of rivers, but they’re everywhere, often now painted to look like cartoon animals, plants or to blend in with the landscape.

The point of all this is to say that Albania has for a long time been on its own, marching to the tune of its own drum, which is why I found it a little curious that it was so hard (for me at least) to identify what “Albanian” really is. Tourist literature features Albanians dancing in national costumes playing traditional instruments, but to my eyes the clothes and bagpipes look very similar to what you see in neighbouring Greece or Macedonia. The food too is a mix of what you find in neighboring Macedonia and Greece, or is kebabs and doners like you find in Turkey. Or pizza and hamburgers.

Any sort of old building or structure in the country is either Roman or, more usually, Ottoman (the Ottomans overwhelmed the Balkan Peninsula between the 14th and 20th centuries, including what’s now Albania). The charming historical towns of Albania, the ones that feature in all the tourist literature like Berat and Gjirokaster, are all Ottoman, with mosques and bazaars. The farm houses in the countryside are not really that old, as most of the really old stuff has fallen down and been rebuilt with cinder blocks and brick.

Not to say that the towns and country aren’t interesting and beautiful, or that the people aren’t lovely, it’s just that I found it hard to identify what, exactly, is Albanian.

I suppose it’s the people themselves. Historians and sociologists and anthropologists (and politicians) all agree there’s a distinct Albanian ethnicity; there are customs and ways of living that differ from others around them. And the people themselves are very quick to point out that they are Albanian. There’s a large and vocal Albanian diaspora, mainly in Italy (where Albanian is the third most widely spoken language), Greece, the US, Turkey and, interestingly, Argentina, but in many other countries as well. So Albania is a place, and Albanians are a people, it’s just hard to figure out exactly how. Where’s their Eiffel Tower or Taj Mahal? What’s their famous national food? What are the stereotypes and cliches everyone is supposed to know? I didn’t see anything that struck me as unique, so it must be the character and ways of the people.

I need more time to think on it. I was in Albania and Kosovo for a little over a month, which is normally long enough to get a feel for a place and to see towns and countryside, but it wasn’t long enough to understand complicated countries in a complicated region. Knowing myself as I do, when I can’t identify something that’s supposed to be identifiable it usually means I’m just not seeing it, not that it’s not there.

Keep your eyes peeled for a future blog post on Albania when I eventually figure it out.

Kosovo

It’s very easy to lump Kosovo in with a post on Albania because, in many ways, they’re the same country. You’d get a punch in the nose if you said the same about Germany and Austria, or Mexico and Guatemala, or (gasp!) Canada and the U.S., but not here. Albanians and Kosovars themselves seem to think of their two countries as cut from the same cloth. Consider: Kosovo is primarily ethnic Albanian too, and Kosovars refer to themselves as “Albanian” (which confused me to no end initially). Albanian is the official language in Kosovo, spoken by 95% of the population. Kosovo, not Albania, was the centre of the “Albanian National Awakening” in the late 19th century.

The history of the peoples in both countries is, up until WW2, more or less the same, and everywhere you go in Kosovo you see Albanian flags and hear Albanian music and see Albanian TV. People come and go across the border continually, their families living on both sides. In fact the quickest way to go between towns in eastern Albania is to drive through Kosovo. Food is the same, the cafés and bars are the same and the way people interact with each other and with me is the same.

Like northeastern Albania, Kosovo is stunning, much of it full of mountains and rivers and lakes and rolling farmland. It’s very beautiful and the people are very warm and welcoming, just like the Albanians in Albania.

Autumn had come to the countryside around Peja, Kosovo, which made for wonderful walking.

I spent one week in Kosovo, visiting three towns – Gjakova, Peja, and Prizren. Prizren is the most visited of the three because it has the most history and culture, the town full of mosques and churches. Gjakova has a marvellous restored market area now full of classy and cozy bars and cafés and little artisan shops. I liked Peja best, mainly because it was just a plain, regular town. It’s a little higher than the others and so I enjoyed a real symphony of colourful leaves and late season light.

But there are some differences in Kosovo: Kosovo is also home to a small minority of ethnic Serbs. While Albania was hunkered down going it alone in the last decades of the last century Kosovo was a part of Yugoslavia and was torn by civil war and ethnic cleansing when that union split apart.

Anyone who read the news during the late 1990s will remember the bloody and protracted war as Serbia fought to keep Kosovo part of its own territory while the ethnic Albanians of Kosovo fought for independence, or to join with Albania. Kosovo eventually declared independence in 2008 but the battle raged on with Serbia refusing to recognize Kosovo. Eventually the US and UN intervened and a ceasefire was brokered.

Kosovo is now classified as a “partially recognized state”, recognized by just 98 of the 193 UN member states; Serbia and 94 other members don’t recognize it (Canada, the U.S., and Britain do). Depending on whose map you’re looking at, the border between the countries is either drawn in a solid line, in a dotted line, or not drawn at all making Kosovo just a part of Serbia. It creates some complications. For example, flying into Kosovo’s capital Pristina is fine, and crossing the border as I did from Albania is fine, but if you then carry on and try to enter Serbia from Kosovo the Serbians will consider you to have entered their territory illegally and send you packing, or worse.

I don’t know how Albanian Kosovars and Serbian Kosovars get along with each other within Kosovo because I didn’t visit the north of the country where the Serbs are, but I’ve read and heard there are still a lot of problems, and sometimes even skirmishes. It’s much easier to think of Kosovo as being Albanian.

Nationhood is not the same as nationality.

Covid-19

Now to address the elephant in the room, Covid-19. There are certainly challenges traveling during Covid, but there are advantages too, the main one being that there are no tourists. For me this is a tremendous positive as, usually, I don’t like visiting touristy places and don’t like mingling with tourists. Albania has been discovered as a tourist destination in the last five years or so, Northern Europeans flocking to the beaches and mountains and charming Ottoman towns and ancient Roman ruins, enjoying bargain prices, so normally you’d expect to find the place hopping. In my pre-trip research I saw YouTube videos of Berat and Gjirokaster and Saranda absolutely heaving with people milling around the souvenir shops and beachside snack stalls. Not so these days. Everywhere was empty. True, I’m here outside the busy summer season but still, there just isn’t anyone around (I wonder why…).

A lot of bigger hotels and popular restaurants are closed, both because of Covid and because the season is over, but there are still plenty of places to eat and plenty of rooms, most very cheap. Things are calm and quiet. Buses are a quarter full. My Air Canada flight from Vancouver to London had a 17% load. When’s the last time you had two entire aisles empty on your transatlantic economy class flight?

There’s no tourist fatigue or any hint of my bothering owners of hotels or restaurants or cafés, they all seem happy (or surprised) to see me. It’s been a very hard year for the tourism business, so even the meagre amount of dosh I splash around is welcome.

There are downsides too. Transportation has been disrupted because people aren’t moving around. For all but the most major routes, instead of 5 buses a day between this town and that there might only be one, or none. It’s impossible to find reliable online information about schedules and routes. Hitchhiking, usually good when you’re a foreigner, proved impossible, no one wanting to share the car with someone whose provenance is unknown. Fair enough. And there are lockdowns and curfews. Tirana introduced a 10pm curfew when I was there the second time, and here in Bulgaria all bars, cafés and restaurants are closed, offering only take-away. Museums are closed. There are no concerts or events. I like to meet locals in bars and cafés and strike up conversations, and I like to accept or propose invitations for cups of tea and meals, but these things aren’t happening now.

It’s all manageable, though, and from my point of view it’s a fair trade to be able to travel.

I think the biggest risk during the pandemic would be needing hospitalization and not getting it, and not just for treatment of Covid. Hospitals are all crammed full with Covid patients; being admitted for anything is not a sure thing when there are long lines of people waiting to get in. Just my luck to dodge Covid for months only to get hit by a car and find no room at the inn.

I don’t want to get sick, and I’m being careful, but I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s a risk I’ve thought about and am willing to take. After all, I take risks when I travel to Africa and India, and despite Covid, malaria, dengue, Ebola, cholera and the others, the average traveler is still more likely to be injured in a road accident than anything else.

Statistics are on my side: I’m not in the high-risk age group (I’m not in the young age group either mind you), I don’t have underlying health issues, I’m generally fit and strong, I don’t smoke and am not overweight. More notable still is the fact that despite being in and out of more hotels and restaurants than I would be at home I’m essentially on my own all the time. I don’t go out in groups, I don’t commute to an office, I don’t attend functions or events, I don’t share a home with anyone – I don’t even have a bubble. Lonely maybe, but fairly safe.

Covid cases and deaths are increasing everyhwere and it’s becoming easy for our imaginations to equate catching Covid with instant death. But I don’t believe that’s the case. The vast majority of people don’t contract Covid, and, of those who do, most are asymptomatic or experience mild to moderate symptoms and recover after a few weeks. And in an odd sort of way I feel less anxious by being away from Canada, away from friends and family, outside of the system, not contributing to the problems and challenges at home. And anyway, it’s not like we’re doing such a good job at home of keeping it at bay.

Travel scratches an itch that I just can’t scratch any other way so, for now at least, I’m happy to be on the road. That’s my story and I’m sticking to it.

Oh, and the travel insurance I bought includes coverage for costs associated with any treatment of Covid-19. When an insurance company agrees to insure you against a risk for a reasonable cost you know the risk can’t be that high… 🙂

So, with fingers crossed I’ll carry on and hopefully be fit and happy enough to post another blog in a month or so.

Stay tuned!

Discover more from The Plain Road

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Beautiful post, very informative! My parents are thinking of buying a condo in Saranda!

LikeLike

Wow! Your world could not be more different than life in Covid-19 Vancouver!

Your blog brings a light on Albania which in my mind has been a dark forbidden country forever. They need you to write for the international hiking community, which I bet would be most interested in these newly emerged walking possibilities.

Thanks for enlarging my lockdown world. Perfect timing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love your post Andrew and stay safe. Lets have a beer when you are in town next Aaron

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Aaron! I didn’t know you were on the list to get my posts. Thanks man. Good to hear from you, I’d love to have a beer in the spring. Hope you guys are all healthy and happy.

LikeLike

Sorry that wasn’t supposed to be anonymous!…it’s Louise !

LikeLike

Hehe. Well thanks Louise.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Really interesting, Andrew…jealous that you are brave enough to travel and explore cool spots like this. Stay healthy, and enjoy the next stage of your journey

LikeLike

Really fascinating Andrew. I’m envious of your freedom and bravery to travel right now.

A very sick mum is currently doing me get back on the road… But I’m looking forward to smaller adventures in the meantime.

I look forward to your next update.

Happy travelling. 🍻

LikeLike

Thanks Simon! You’re no stranger to interesting blog posts yourself and I look fwd to reading yours when you’re eventually back on the road.

LikeLiked by 1 person