Oh boy, where to begin…

It’s difficult to write about my experiences and impressions of Istanbul, because I find it hard to know where to start. Like the city itself, staying focused on writing, and not jumping all over the place, is a challenge. Exploring Istanbul as a visitor is like that: you start the day intending to walk around such-and-such a neighborhood, but while there you see something shiny in the distance and wander over, for just a moment. Before you know it you’re somewhere else, finding some other amazing thing.

It takes a lot of discipline to explore a city like Istanbul, as silly as that sounds. I’m all for wandering around and letting the road take me where it may, and in a lesser city that approach works fine. Not in Istanbul. There are too many compelling things to see, too many cool neighborhoods; if you just drift you end up frustrated and left without a coherent picture of the city. There’s simply too much there to process if you just let it flow past. I think the best way I can describe Istanbul is to say that it’s thick. There is such an abundance of flavors and sights, it’s like a thick stew, or a heavy soup. Each spoonful dredges up something else, over and over again, and you never seem to find the bottom.

The charming cobblestone back alley streets near the Edirnekapı neighborhood.

Typical street in the Fener area; most streets are quite busy, but usually tidy and organized.

Restaurant on the bottom, old residence on the top. As Istanbul develops it starts at the commercial level first. This place is in the Sarıyer district.

I’d been to Istanbul three times. This time, my fourth, I stayed for an entire month, which is my longest visit by two weeks. You’d think it would get easier, describing a place with each passing visit, but for me it gets a little harder, I suppose because each time I see more and learn different things. This stay was especially fruitful for discovery, and I learned more about the physical city and its history than ever before. Using my rented Airbnb apartment as a base I set off every single day on hours-long explorations, ultimately visiting at least a corner of nearly every single neighborhood. I can’t count how many times I turned a corner and said, aloud, “Oh…wow!” It’s thick. Everyday it was something else. And on the days I returned to a place I’d already been, it was even more rewarding. You can’t say that about any old city.

Back streets in Kasımpaşa, close to my rented apartment. Despite being a megacity of over 15 million, it’s easy to find quiet corners anywhere.

So, what do I think about Istanbul? You have to start somewhere, I suppose, so here goes.

First, a little history

It’s impossible to make heads or tails of Istanbul without knowing just a little of its history.

Istanbul started out as Byzantion, a small Greek fishing village settled around 667 BCE (actually, it was settled even earlier than that, by Thracian or Illyrian peoples, but it was small and largely insignificant). Roman Emperor Septimius Severus expanded the city in 196 CE (read: captured it and made it more Roman); he was impressed with its strategic location that allowed for control of several important trade and military waterways.

In 285 CE the Roman Emperor Diocletian created a new system to govern his massive empire by creating western and eastern administration zones, and made Byzantium the capital of the eastern district. Later, in 330 CE, the Emperor Constantine renamed the city Constantinople (after himself, why not?) and moved the centre of the entire empire to his new capital. In 395 the Emperor Theodosius formally split the mighty Roman Empire into two, west and east, and Constantinople became the Greek speaking capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, also called the Byzantine Empire. The combination of imperial power and a key location at the crossing point between the continents of Europe and Asia, and later Africa and other regions, played an important role in terms of commerce, culture, diplomacy, and strategy. It was the center of the Greek world and, for most of the Byzantine period, the largest city in Europe. The Western Roman Empire withered and died around 476 leaving Constantinople as the capital of what remained. The Eastern Roman Empire, and the Byzantine Empire, are terms used interchangeably.

Typical Ottoman Sultan in his finery (public domain photo)

Over the centuries The Byzantine Empire declined in power as the Ottoman Empire expanded, gobbling up most of what was left of the Roman world until all that remained were a few bits and pieces in present day Greece, some islands in the Aegean and Mediterranean, and Constantinople. Still mighty, Constantinople was the most coveted city in the Balkans, and the one treasure the Ottomans couldn’t absorb, due mainly to its massive fortifications and strategic location.

But finally it fell. The young Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II captured Constantinople in May of 1453 after a six-week siege (he was known from then on as “Mehmed the Conqueror”). He declared the city the new capital of his Empire, Muslim and Turkish speaking, and renamed the city Istanbul. It remained the Ottoman capital until 1923 when the Ottoman Empire ceased and became the Republic of Turkey with her new capital in Ankara, as it is today.

There are still Roman/Byzantine things to see in Istanbul, but most of what today’s visitors see—the mosques, the palaces, the parks and gardens—are Ottoman.

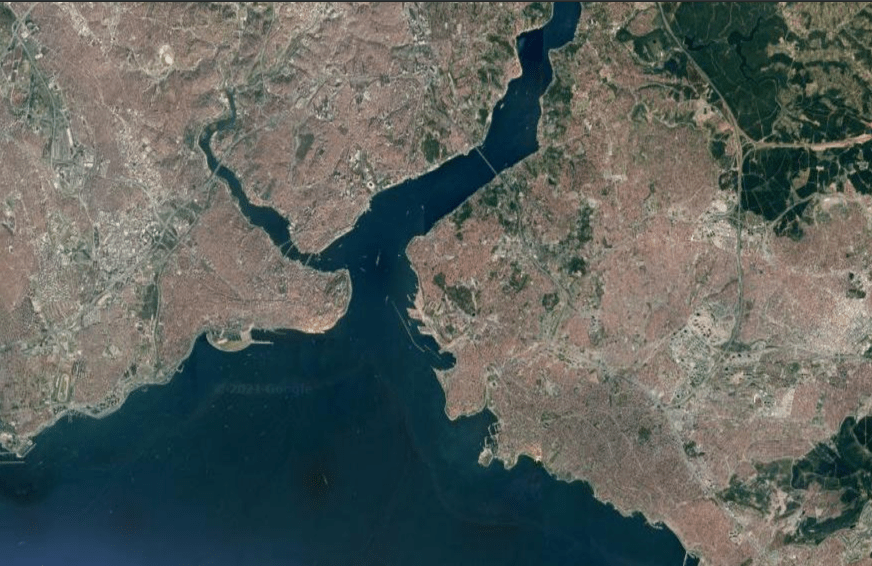

Orientation

Istanbul spreads across two continents. There’s a European side (sometimes referred to as Thrace), and an Asian side (sometimes referred to as Anatolia) separated by the Bosporus Strait, a 31 km north-south finger of water that, in addition to separating the two continents, connects the Sea of Marmara with the Black Sea. The Sea of Marmara in turn connects Istanbul to the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas. Around 65% of Istanbul residents live on the European side, the rest call Asia home. The main historical section of Istanbul, Old Istanbul, with most of the famous mosques and palaces, is on the European side.

The greater Istanbul metropolitan area is a little over 5.3 million square kilometers and home to 15.5 million people, but the area most visitors are interested in is much smaller. I’m not most visitors, however, so to me Istanbul is large. There’s an excellent transportation system, which includes a metro, street level trams, buses, ferryboats and cable cars, so it’s very easy to move between Europe and Asia on land, on sea, and under the sea, making exploration on a grand scale very doable.

Istanbul is quite hilly; other than the many seaside promenades there’s not much anywhere that can be described as flat. Steep steps connect neighborhoods nestled horizontally on precarious hillsides, creating “layers” of neighborhoods.

Much of Istanbul is very hilly and connected by steep stairs, like these ones near Beşiktaş.

I stayed in the Tarlabaşı neighborhood on the European side in a rented Airbnb apartment for a little over one month, from February 19 to March 26.

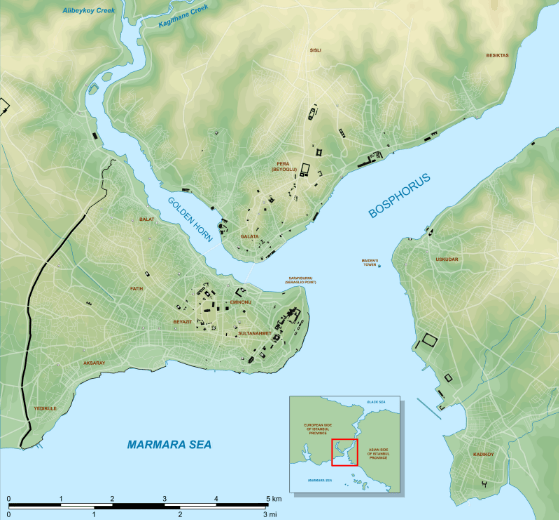

Layout of Istanbul; “Istanbul” is on the European side, “Uskudar” on the Asian side.

Getting Around

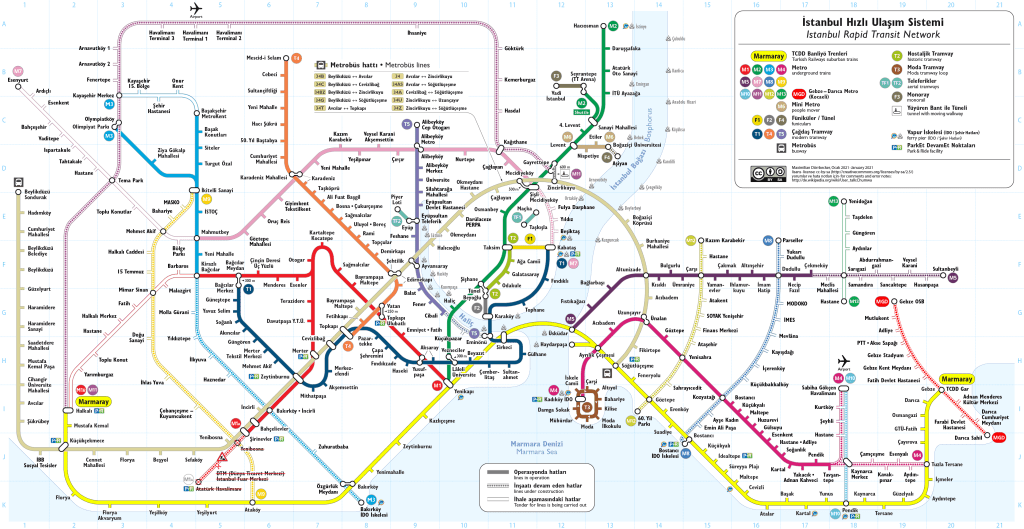

Since my last visit to Istanbul the transportation system has become much simpler to use due to the adoption of a smart card for fare payment. The Istanbul Kart is a rechargeable smart card similar to an Oyster Card in London, or a Compass Card in Vancouver. You add credit to the card at a machine, tap a sensor each time you enter a bus or a train or a boat and the machine automatically deducts the correct fare.

The system is excellent. There are subway lines, trams, boats, and a million buses. You can download an app for your phone (in English) that helps you navigate, check departure times, figure out distances, and how to stitch together the various types of transport for a journey anywhere in the greater Istanbul area. I became a power user, and moved around the city quickly and efficiently. I’d walk to a boat dock, take a ferry across some body of water, get on a subway for a few stops, then find a bus. Learning the system and using the Istanbul Kart was the key to being able to explore as widely as I did.

Map of the Istanbul Metro, Tram and express bus system. It’s easy getting around the city.

Boats offer the most pleasant way to get around, by far, though they’re generally fairly slow, except during rush hour when they can be much quicker than surface travel. During global pandemics they’re also much safer, as you can sit outside on deck in the fresh air rather than crammed in on a metro. And they go everywhere, up the Golden Horn, up and down the Bosporus, across the Sea of Marmara to the Asian side of the city, and many places in between.

Inside one of the many ferryboats plying the waterways of the Greater Istanbul area. This is on-board a medium sized boat; some are much smaller, and some much larger. Ferryboat is a very comfortable way to travel.

Bus exchange in the Alibeykoy neighborhood, north of the Golden Horn. This is a typical growing middle class area of Istanbul. Buses unlock the door to getting anywhere in the city.

Neighborhood Creep

Istanbul has a population of a little over 15 million, making it the most populous city in Europe and the fifteenth largest city in the world. It’s classified as a megacity (a megacity is typically defined as a large city with a population over ten million). It didn’t just start that way, though. When the Ottomans captured Constantinople from the Byzantine Romans in 1453 the city was home to a little more than 50,000 people. Once it became the new capital of the Ottoman empire it started growing and, with a few interruptions, hasn’t stopped.

It gobbled up neighboring villages and towns as it grew, and places that were at one time separate merged to become part of the big city. Today everything is jumbled together, though many of the gobbled-up villages still maintain their individual flavor. Fener, Balat, Sarıyer, Eyüp, Üsküdar, Kadıköy, Maltepe (some of my favorites, incidentally)…there’s a long list of Istanbul neighborhoods that at one time were on their own. And because the development of the city has happened over such a long period of time, the different neighborhoods have changed at different times, and at a different pace. They all have a different story, which is what makes exploring Istanbul so interesting. Even I as a foreigner I can tell—and feel—the difference from neighborhood to neighborhood.

Tending to the neighborhood; Fener.

The streets of Fener are full of historic wooden mansions, churches, and synagogues left over from the Byzantine and Ottoman eras. Many of the fanciest houses were largely destroyed when they widened the streets in the 1930s, but there are still plenty left (it’s hard to imagine the streets any narrower than they are today). Many houses been beautifully restored and painted in bright colours.

The colorful streets of the Balat neighborhood.

To the north of Fener is Balat, the former main Jewish quarter of Istanbul. Jews persecuted under the Spanish Inquisition in the late 15th century were welcomed to Istanbul by the Ottoman Sultan, who even sent his fleet to Spain to rescue them (Sultan Mehmed II had a Utopian vision for what he wanted his new capital to become, filled with people from different walks of life, religion and culture). Balat was the largest district of the Sephardic Jewish community in Istanbul, and there are still three active synagogues in Balat (sadly all closed to visitors when I was there, due to the pandemic).

Typical Balat streets.

A cup of (western) Joe to fortify myself while exploring the streets of Beyoğlu.

These days Balat is one of the hippest bohemian neighborhoods in Istanbul, and one of the best tended to since a UNESCO plan started in the early 2000s spurred the restoration of many of the most charming old buildings. A Turkish TV series really put the place back on the map (called “Cukur”, I haven’t seen it). Walking around Balat today you find dozens of charming little cafes and bars and cute little shops selling cute little items of food and housewares that the oh-so-cool-and-hip just can’t live without.

Sarıyer is the northernmost district of Istanbul, on the European side of the city. It includes a huge area that takes up much of the west side of the Bosporus all the way to the Black Sea. There are delightful little neighborhoods in Sarıyer, with delightful and hard to pronounce names, places that were once villages: Rumelikavağı, Garipçe, Rumelifeneri, Demirciköy, Zekeriyaköy, Bahçeköy, Kilyos, Kumköy, Uskumruköy, Gümüşdere, and Kısırkaya.

There’s also a neighborhood actually called Sarıyer. During most of its history, Sarıyer was a fishing village. Now it’s a quiet and extremely calm and pleasant place, with a long seaside promenade and some very nice parks and museums. There are still a lot of small fishing boats and seafood restaurants. It was pretty quiet the few times I wandered around the district, but I was told in normal, non-pandemic times it can get very busy with people eating fish and walking along the docks and seaside, particularly on the weekend. The neighborhoods in the district beside the Bosporus remind me of Victoria, Canada, calm, tidy and pretty.

The Sarıyer district is quickly gentrifying but there are still many small working fishing ports.

The Eyüp neighborhood is an historically important area for Turkey’s Muslims, as there are several tombs there, “rediscovered” by the Ottomans when they took Constantinople in 1453. Relics are displayed in the Eyüp Sultan Mosque, including a stone said to bear the footprint of the Prophet Mohammad (I didn’t see it). There are a lot of Turkish religious pilgrims milling about, especially at Friday prayer, and especially before weddings or circumcisions. I wasn’t there to pray, and I’ve been both circumcised and married in the past (not on the same day), so thankfully my visits were able to take place in a strictly recreational capacity.

The Eyüp Sultan Mosque in Eyüp. On the northwest side of the Golden Horn, Eyüp is a conservative Muslim area of the city but is full of friendly families and wonderful Ottoman architecture.

There’s an enormous graveyard in Eyüp, the Eyüp Cemetery, located there because at one time Eyüp was in the countryside. It’s massive, and very beautifully leafy and green. If you’ve read any of my blog posts you know I like wandering through cemeteries. This one is a real winner, perched high up above the Golden Horn, surrounded by trees and fresh breezes.

The views back down to the Golden Horn from the calm and pleasant Eyüp cemetery.

The district of Üsküdar is one of Istanbul’s oldest-established residential areas, founded in the 7th century BCE by Greek colonists, long before Byzantium. It’s on the Asian side of the city, directly across the Bosporus from Old Istanbul. It’s easy to reach by ferry or metro. There are a lot of retired people there, as well as middle class folk who commute to the European side for work or school. Rent is much cheaper than on the European side. During rush hour the waterfront bustles with people running to and from ferries and buses. Üsküdar also has the smell of the sea, the sound of foghorns, motorboats and seagulls and one of the best views back across the water to other parts of Istanbul.

Waiting for something grilled in the Kasımpaşa neighborhood.

Kadıköy also sits on the Asian side, just south of Üsküdar. It too was founded a long time before Byzantium, but it has a much different flavor than Üsküdar because of its bars, cinemas, murals, restaurants and cozy bookshops. It’s the cultural center of the Asian side of Istanbul. There are a handful of wonderful cobbled streets lined with dozens of great little cafes, many of them fighting with each other for customers who come to drink Turkish coffee (yes, even the Turks call it Turkish coffee, “Türk kahvesi”). The tables at the cafes were spaced oh-so-perfectly to provide some social distance, but they still allowed for the enjoyment of the charm of the neighborhood. The afternoon I visited it was warm and dry and sunny so I sat for a long time people-watching.

Istanbul is still chilly in February (it snowed a week before I arrived), but on many days a warm afternoon sun makes an appearance and gives residents a chance to enjoy an outdoor drink, like these loafers are doing in one of the many backstreets of Beyoğlu.

A little farther down the coast from Üsküdar and Kadıköy is Maltepe, another old place that predates Istanbul. This part of the coast has been a retreat from the city since Byzantine and Ottoman times, and right up until the 1970s was a rural area dotted with summer homes for wealthy Istanbul residents. It’s now on the suburban railway line and much more middle class. It’s dead easy to reach from other parts of the city making it a favourite spot for day-trippers or weekenders who come to visit the beach. It was much too cold to swim in the sea when I was there (and the water is pretty dirty), but there’s an extremely long seaside promenade and dozens of parks, tennis courts, skateboard parks, children’s playgrounds, and plenty of places to sit with a tea or coffee or a beer.

Efes Pilsen isn’t a very good beer, but it goes down easy after a long day of pedestrian exploration. I enjoyed this one in Beyoğlu.

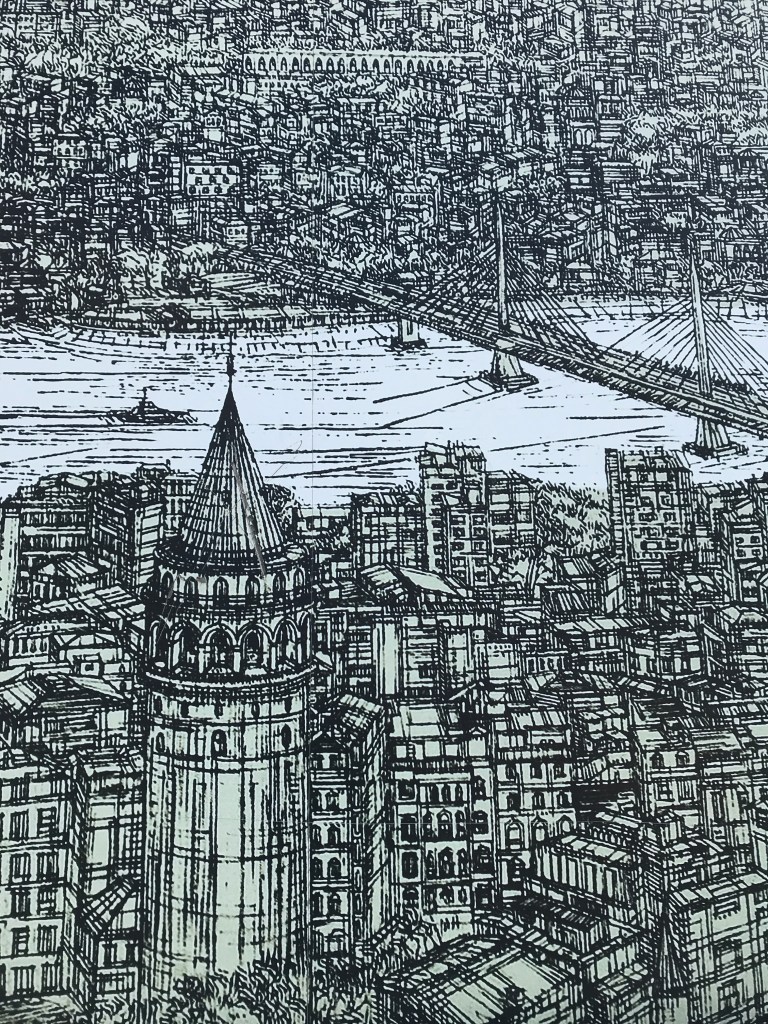

Beyoğlu is a district on the European side of Istanbul, across the Golden Horn from the old city. In older times it was known as Pera, (meaning “beyond” in Greek). Pera surrounds the ancient coastal town of Galata, which became the base of European merchants, particularly from Genoa and Venice. In 1348 the Genoese built the famous Galata Tower, one of the most prominent landmarks and tourist sites of Istanbul. Pera (or Galata as it was sometimes called) remained under Genoese control until 1453 when it was captured by the Ottomans along with the rest of the city (the Genoese were allowed to stay but became subject to Ottoman law).

The old district of Pera, now Beyoğlu, was at one time the most European district of the city; you can still see flavors of Paris, Rome and Madrid here and there, though it’s still decidedly Turkish.

During the 19th century it was again home to many European traders, and there were a lot of western embassies, especially along the Grande Rue de Pera (today İstiklâl Avenue), making the area the most Westernized part of Constantinople, especially when compared to the older parts of the city on the other side of the Golden Horn. Pera was one of the first parts of Constantinople to have telephone lines, electricity, trams, municipal government and even an underground railway, the “Tünel”, inaugurated in 1875 as the world’s second subway line (after London’s Underground) to carry the people of Pera up and down from the port of Galata and the nearby business and banking district of Karaköy. You can still ride it today (using the Istanbul Kart!).

“This is my mansion, please don’t damage it” – Turks are crazy about cats, and there are thousands of street cats in every Turkish city and town. Many residents regularly fill bowls with food and water, and groups provide shelter for them, like these enjoyed by feline squatters in Karaköy.

Beyoğlu is a very touristy part of town, but the vast majority of tourists go to a very small number of places. It’s a bit like like the Eiffel Tower, or Taj Mahal: everyone goes there but for some reason ignores all the other amazingly cool stuff to be found within a half kilometer radius. Even during Covid the area of town near the Galata tower was always quite crowded. There are some very hip and trendy neighborhoods in Beyoğlu, like Cihangir with its fashionable Bohemian (but slightly tatty-on-purpose) cafes and used clothing shops.

Old meets new: the Galata Tower seen rising above the hip and groovy streets of Karaköy.

Painting the side of her building near Hasköy Park.

There are still plenty of traditional tea and coffee houses in Istanbul, but coffee culture has really taken off. There are hundreds of hip and oh-so-cool cafes everywhere, like this place in Cihangir.

Taking a short break in Cihangir.

The Water

One of the things that makes Istanbul so attractive and charming is all the water the city is built around. Sadly much of it is too polluted for swimming (though the locals tell me there are places to go that are safe for swimming in the summer), but it looks attractive, and the shimmering water and lapping sound it makes against the shore adds mightily to the charm. And the names of the various seas and inlets are wonderful: the Bosporus, the Golden Horn, Kagithane Creek, the Sea of Marmara, the Black Sea…cool!

Ferryboats docked and waiting for their chance to serve. Ferries cover every nook and cranny of water in Istanbul.

They’re all different, too. The Sea of Marmara is massive, like an ocean, its far shores invisible. Same with the Black Sea. The Bosporus is only 700 meters wide at its widest, so you can easily see across. It’s an incredibly busy shipping lane, providing dramatic, close-up views of massive ocean going vessels plowing up and down the narrow straight (The Bosporus is the world’s narrowest strait used for international navigation, though there’s currently a new—and controversial—project underway to create a canal west of the Bosporus that would carry all major maritime transport. See here).

The Golden Horn looks a lot like a river, though in actual fact it’s an inlet of the Bosporus. It too is very busy, but mainly with pedestrian ferry and small boat traffic. When Istanbul was Constantinople most of the population was concentrated on the west side of the Golden Horn, but nowadays both sides are heavily settled with industry, residential neighborhoods, parks, restaurants and docks. Until the 1980s, the Golden Horn was polluted with industrial waste from the factories, warehouses, and shipyards along its shores. It’s been cleaned, though, and the local fish, wildlife, and flora have largely been restored. It looks clean.

Views of Karaköy from the deck of a ferry. Traveling by boat gives you a chance to see the city from the water.

Water also means fishing, and though the main commercial fishing fleets have moved up to the Black Sea and farther south and west along the Sea of Marmara there are still loads of smaller but serious commercial fishing boats, as well as largish pleasure craft and sailboats. There are many marinas on all the waterways, and seafood restaurants everywhere (not much of the fish locals eat actually comes from any of the waters near Istanbul, apparently).

Best of all, the water brings fresh air and cooling breezes to the city during the hot summer months. It was winter when I was there on this trip, and usually quite chilly near the water, but I’ve been to Istanbul in the summer when it’s hot and sticky. Walking along one of the seaside pedestrian areas with an ice cream quickly chases away the sticky daytime heat.

“It’s cold, do I really have to head out to sea?” Old man and a boat in Sarıyer.

Highlights

Here are just a few highlights of some of the days I spent on this visit, too many to list.

Shopping in Kasımpaşa – after a 15 minute walk downhill from my Airbnb place you reach the neighborhood of Kasımpaşa (pronounced “kas-uhm-pasha”). Kasımpaşa is an old naval/maritime residential area, and very historic; there are still working shipyards and ferry docks and rusty old boats slipping past on the Golden Horn. In the 1950s and 1960s, Kasımpaşa was a working-class area, especially for sailors and people working in the harbor. It’s still working class, though the focus is no longer on the navy. I stumbled on the neighborhood one day and loved it, and it became my main shopping area. It has everything: a handful of bakeries and butchers, a few fruit & vegetable places, a small grocery store, delicatessens (called ”şarküteri” in Turkish, from the French “charcuterie”), a few cafes (some slightly modern and hip for the younger crowd, some simple tea houses for the older crowd), a çiğ köfte place (çiğ köfte is a sort of vegetarian meatball made of bulgur, tomato paste, pepper paste, pomegranate syrup and lots of spices), a doner place, a hardware store, a pizza place and a few clothing stores. There’s a large square with a fountain where kids chase pigeons. It was always buzzing with local people.

One of the bakeries was much busier than the others and usually had a line of shoppers snaking out the door and down the sidewalk. Most customers appeared to be housewives, many in hijab. I’m usually not one for waiting in line, but this place really was worth it. Their bread was excellent, and they had a few darker and grainier loafs than you find at the usual Turkish bakeries, as well as good pastries, cakes, and cookies. Once in the store I know enough Turkish to point and say, “Hello, good afternoon, I’d like one of these, and two of those, please,”

The hilly streets of Kasımpaşa. My apartment (not visible) is just up the hill to the left.

Shopping in Kasımpaşa. In general the quality and variety of food and groceries available in markets and shops all over Istanbul is outstanding.

Özmar convenience store. I shopped for my groceries farther down the hill in the center of Kasımpaşa, but the Özmar was the closest place to me for quick supplies of water, milk, beer and snacks; family run and very welcoming and friendly.

The loaf of bread was the last thing I needed that day, so I invited my bread and fruits and vegetables to come sit with me at one of the outdoor tables on the square where I enjoyed a large cup of tea. I felt like a local. I bought the same things the local people did, from the same places they buy their things. I could speak enough Turkish to ask for the things I needed, and I knew where to find them. I wasn’t on holiday, I wasn’t seeing something historic or important, I wasn’t trying to find anything; I had my own little apartment nearby and was happy, safe, content and engaged. It was a great slice of a regular day in Istanbul. If I moved to Istanbul permanently I would look for a place to live near Kasımpaşa.

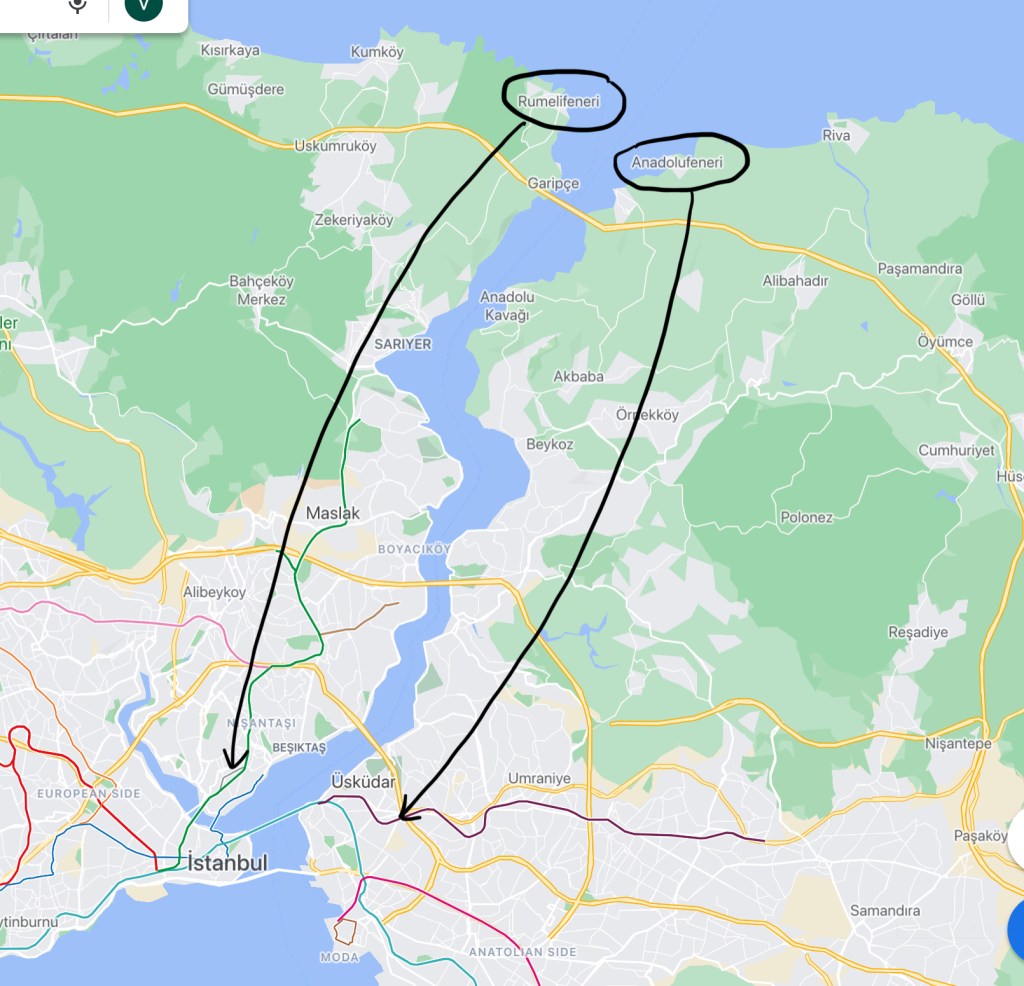

Both sides of Bosporus – I went all the way to the Black Sea on a city bus. In fact I went twice, one day on the western, European side of the Bosporus, and once sticking to the eastern, Asian side. On the European side you can take the M2 metro line to the last stop (Hacıosman) then catch a bus from there that goes all the way north to a village called Rumilifeneri right on the Black Sea. There’s no metro on the Asian side that runs north, so you have to take two buses; the first one fights its way through a fairly busy part of Üsküdar, but the second one weaves its way over hill and dale through countless little neighborhoods and finally arrives in Anadolufeneri, where I could peer back across the Bosporus to Rumilifeneri on the other side, where I’d already been a few days earlier. By the time you reach either place the city has long gone and there is nothing but trees, bush, and little farmhouses and small plots of land. Both journeys take around 90 minutes and cost about two dollars.

Rumelifeneri and Anadolufeneri, the two villages on the Black Sea I visited, getting to both places on the city bus.

The Bosporus is 3.7 km (2.3 miles) from side to side at the point where it opens into the Black Sea. The canons the Ottomans used couldn’t reach from the shore to the middle of the Bosporus, so if intruding ships stuck to the middle they could sneak through. To remedy this the Ottomans built towers spaced evenly along both sides of the strait. When a ship entered the Bosporus from the Black Sea a soldier in the first tower would signal to the next tower using a series of flags which identified whether the ship was friend or foe. The straight narrows as it gets closer to Istanbul, so eventually the canons could reach, and the Ottomans would be able to blast an uninvited ship to smithereens. Rumilifeneri and Anadolufeneri were tower outposts where the flag notifications started.

There’s a ruined fortress in Rumilifeneri built in 1768 that you can wander through, though there was a pack of sinister looking dogs eyeing me when I went in so I gave the place a very quick and cursory once-over from a distance (it’s another way you know you’re in a village: stray dogs never bother you when you’re in a city in Turkey, but they can be vicious when you find them in the countryside). The village itself was very small but quaint, right on the Black Sea. I got the idea that it got busy with Istanbul residents in warmer months, and when there wasn’t a killer virus in town.

Anadolufeneri, on the other side, is more interesting. They were filming a Turkish television show the day I stumbled into town, so I sat in the outdoor courtyard of a small tea house with a bunch of other locals and watched (repeatedly) a car drive up to a shop, stop, three bad guys dressed in black suits get out and go with purpose into the shop, clearly with sinister bad-guy intentions. They must have done five takes. When the shooting was over and we were all allowed to go about our business I went down to the beach and looked back across the Bosporus at Rumilifeneri.

Village house in Anadaolufeneri.

The Black Sea looks impossibly large, like an ocean stretching to the horizon. In my mind I traced the contour of the shore northwest to Bulgaria where I’d come from a month earlier, then east to the other Black Sea towns I’d visited in Turkey on previous visits—Samsun, Ordu, Giresun, Trabzon, Rize—all the way to Georgia. The Black Sea has always been a busy and extremely important strategic waterway on the crossroads of the ancient world, but where I stood on the shores of those two little villages it was quiet and uneventful. And I got there on the bus.

Fearless Canadian explorer conquering the banks of the Black Sea just outside the village of Rumelifeneri.

Turkish coffee in Asia – Turkish coffee is easy to find in Turkey. It’s not just a touristy thing, Turks themselves drink it at home and in cafes and in restaurants. It’s served in small cups and is thick and sweet, and there’s a solid layer of sludge that loiters at the bottom of the cup (it’s essentially the same as Greek coffee, but don’t tell the Greeks or Turks that). You sip the coffee, the way you do an espresso. Usually the coffee comes with a small piece of lokum (Turkish delight), or a few chocolate covered almonds, or something sweet. The quality and taste vary from place to place, depending (I was told) on the coffee used, the grind, the water, the temperature of the water, and the type of pot. On paper it’s an easy thing to make, but it requires more art than science. The best coffee is made in a copper pot, called a cezve, and the real secret is (they say) the grind of the beans. A single bean for Turkish coffee is ground down to 45,000 particles, like baby powder (which I initially found impossible to believe, but Google agrees); espresso calls for 3,000 particles per bean, and drip coffee a measly 100.

A fortifying cup of Turkish coffee in one of the many charming coffee houses in Kadıköy.

Across the Bosporus on the Asian side of Istanbul in Kadıköy is where I drank the best Turkish coffee. Kadıköy has a lot of small bars and restaurants and cafes all jumbled together on several atmospheric streets, Serasker Street the main one. There’s a famous coffee place there called Fazil Bey. When I searched for “best Turkish coffee in Istanbul” Fazil Bey kept coming up, in both English and Turkish searches. Being the travel snob I am I was immediately skeptical, but curious, so I went for a cup. Damned if it wasn’t delicious! Fazil Bey is very small (they have several branches, though), but bright and cheerful, with a half dozen tables set out on the street. Their coffee is about 20% more expensive than it is in less well known places, but the coffee was truly excellent. I had two cups. Sitting and sipping and enjoying the atmosphere I noticed there were several other Turkish coffee places in the immediate vicinity, competing for business. That sort of competition usually rewards the consumer, so I set off to try some of the others. All in all I had six—count ’em, six—cups of coffee that afternoon, over a two-and-a-half hour period, drifting from place to place. Fazil Bey was the best, I have to say, though another nearby place called Niyazi Alaca’nın came a very close second.

The Architecture – There is a long list of notable buildings in Istanbul. To start with, there is an enormous amount of ancient Roman and Greek stuff all over the place; in fact, there is such an abundance of buildings and ruins that it’s usual to find columns and other chunks of marble sitting unnoticed in empty fields, in ditches, and beside the roads. Home owners prop up stubby sections of Roman columns to use as pedestals for plant pots. Laundry lines are strung between Greek ruins. Some of it has been preserved, of course, and all over Turkey, including in Istanbul, you can visit ancient forums and hippodromes and aqueducts.

Modern Istanbul is home to a number of significant contemporary buildings. A lot of the really cool modern designs involve renovations and expansions of old Ottoman buildings, creating an “old and new” feel (here’s a link to an interesting page on architecture and design in Istanbul: https://www.dezeen.com/tag/istanbul/)

But the big architecture draw in Istanbul is the huge collection of Ottoman structures, particularly the mosques. The image of minarets soaring into the sky, silhouetted against a red-orange sunset high above the Golden Horn as the sun hangs warm and dusty in the air is about as classic a picture of Istanbul as you can get. I’ve been to Turkey five times, and I still get goosebumps when I see one of the massive Ottoman mosques and hear the call to prayer. What I like most about the mosques is that they’re so large and commanding but at the same time they’re very simple, inside and out. Now and then you see one with more baroque styling here and there, and they all have some degree of calligraphy on the walls (usually passages from the Koran), but in general they’re very modest and understated.

The lucky residents of Istanbul have places like this grassy area behind the Süleymaniye Mosque to sit and eat their lunch.

When you enter a traditional Catholic church in Italy or Mexico you’re met with paintings and candles and ornamentation and elaborate carvings and icons. It’s busy and alive and glittery. When you enter the courtyard and interior of a large Ottoman mosque in Istanbul you’re struck with the simplicity of the thing, the quiet and calm. Mosques don’t have pews, chairs or paintings. It’s not to say that they’re solely functional, but the beauty and celebration is found in the empty space and solemnity of the buildings, which makes them all the more bold and magnificent. I’ve been inside every major mosque in Istanbul—most more than once—and many of the lesser ones as well.

Not all mosques in Istanbul are grand and important, but to me they’re all equally calm, peaceful and elegant.

Courtyard of the Çamlıca Mosque, high up on Çamlıca Hill in Üsküdar on the Asian side. Opened in March, 2019, the Çamlıca mosque is currently the largest mosque in Turkey.

Hagia Sophia is of course the most famous of all the famous buildings in Istanbul. In Turkish it’s called Ayasofya (“Ayasofya-i Kebir Cami-i Şerifi”, to give it its full name). It was built as a church by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I in 537 CE. For many years it was the largest Christian building in the world. The first four times I visited Istanbul Hagia Sophia was a museum (an expensive museum). Last year, however, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan ordered that it be turned back into a working mosque, which means, like every other mosque in Turkey, entry is free and unrestricted. There was a fair amount of controversy over this. Erdoğan’s critics regularly attack him for pushing secular Turkey towards Islamisization. Turning the country’s most famous museum landmark back into a mosque, when there are plenty of other mosques nearby, fuels their fire. I see their point for sure, and even as an outsider I have to agree that Erdoğan is threatening the secular independence of Turkey, something that’s guaranteed in their constitution. But being able to enter Hagia Sophia whenever you like, and being able to stay for as long as you like is certainly a plus. There aren’t a lot of large buildings in the world dating from the 6th century, and wandering in and out of Hagia Sophia, and standing under its massive dome is truly remarkable. If only it could talk…

Interior of 6th century Hagia Sophia, or Ayasofya, the jewel in the crown of the wonderful architecture you find in Istanbul.

Comparing notes and making a plan outside Hagia Sophia.

Not all buildings in Istanbul are grand and up-to-date, though I’ll bet this one was once marvelous.

Walls of Constantinople – One of the things that’s so cool about the history in Istanbul is that with very little imagination, you can actually see what happened, not just read about it. A case in point are the Walls.

The Walls of Constantinople are a series of defensive stone walls that have surrounded and protected the city since its founding. The walls were the last great fortification system of antiquity, and one of the most complex and elaborate systems ever built. They were legendary, and known—and proven—to be impenetrable. Many tried and failed to sack the city, and it wasn’t until May of 1453 that it finally fell after a six-week siege from the sheer weight of numbers of the Ottoman forces (and their large canons).

I visited several sections of the walls that are still standing more or less untouched since the siege. A few short sections that crumbled have been repaired, including the main gate where Mehmed entered his newly conquered city, but most of the walls stand now as they did back in 1453. The Ottomans concentrated their large canons and troops mainly on just one area of walls in the far west of the city (the “land” walls, as opposed to the walls that encircled the city from the sea) and pounded them relentlessly until they finally got in, so the other sections were largely ignored and undamaged. A large parcel of empty land adjacent to the walls has been set aside as a Historical Area of Istanbul, and a World Heritage Site, and is still a grassy field, the way it would have been back when the Ottomans were attacking. There’s now a major highway running alongside the field, and the modern city of Istanbul stretches far beyond, but back in 1453 this was outside the city, in forested lands.

The Walls of Constantinople, still standing after all these years (and all those sieges).

Residents walk alongside the Walls, on the inside of the city.

That’s all well and good on paper, but in reality it’s magical. You can stand in the field and look east at the massive stone walls, standing imposing as they would have looked to Mehmed as his canons thumped away. When the Byzantines finally gave up, Mehmed entered the city through the Gate of Charisius and walked straight to the Church of Hagia Sophia and converted it, on the spot, to a mosque. You can stand in the field and see the walls and know that on the other side the Roman Empire ceased to exist in the early morning hours of May 29, 1453, in Istanbul, at the very spot you’re now standing. It’s sobering. Historians don’t all agree on the precise date or place the Roman Republic began, but they do agree on when the Empire ended, and I’ve seen where. Istanbul has those sorts of treasures.

The Turks

I suppose in general the Turkish people you interact with in Istanbul are not much different from the ones you find in other parts of the country. They’re big city folk, though, so perhaps they’re a little busier. Istanbul is the only place in Turkey (that I’ve been) that you can call truly cosmopolitan. Ankara, the capital of Turkey, is big, and there are a lot of embassies there, and people from neighboring countries in town to get visas and make applications, but I don’t think it’s really multi-ethnic or cosmopolitan the way Istanbul is.

Local resident going about her business in the Sultanahmet neighborhood in Old Istanbul.

Most people in Istanbul are ethnic Turks, of course, but there are Kurds, Armenians, Jews, and Arabs, and northern looking Europeans and a smattering of other types of people. Turkey took in an enormous number of Syrian and Iraqi refugees; many of them have assimilated into the culture and society so (to me) they’re now unidentifiable, but they’re there, and according to Turkish people I spoke with, they add a lot of local colour and variety.

Even the cats of Istanbul are proud of their city’s wonderful heritage.

There are quite a few black people in Istanbul, most I think from African countries (I heard groups of them speaking together, not in English, Turkish, Arabic or French, so I assumed they were speaking some sort of African language). There are European and North American residents as well, Brits, Scandinavians, French and others. I saw restaurants serving Uighur and Chinese food, sushi (untested by me), Mexican, Indian, Thai and other big city cuisines. There are Asian people here and there as well, mostly Chinese I think. There was a Chinese supermarket near one of the metro stations. It’s not London, New York, Vancouver or Melbourne, but Istanbul has some international goings on.

Brushing up on a few passages from the Koran, or checking the football scores in the courtyard of the Ismail Aga Mosque in Fatih.

It’s a generalization, of course, but my opinion of Turks, from several visits to their country, is that they’re unfailingly patient and cheerful, gentle with children and animals, polite and warm, and very helpful. I know enough Turkish to say who I am and where I’m from and what I’m doing in Turkey, and I can order food and things from the shops and ask for directions. Turks in Istanbul were a little less impressed with my language skills than those in smaller towns, I think because they’re more used to foreigners living in their city and speaking Turkish (and/or my Turkish is poor). My feeling is that Istanbul is an extremely easy city to be in as a foreigner, though I’m sure it depends somewhat on what sort of foreigner you are, and how hard you try to fit in and make the place home.

My rented Airbnb apartment near Kasımpaşa; I had this baby for an entire month.

A fixer-upper in Kasımpaşa.

Covid

Two weeks before I left Istanbul to return home the Turkish government relaxed some of the health restrictions that had been in place the entire three months I’d been in Turkey. Restaurants and tea houses and cafes and bars were again allowed to open for indoor dining; before that it had been takeaway only. Strict Covid prevention measures had brought the number of daily new cases down to a more manageable level, so they relaxed. It probably wasn’t the best idea, as suddenly—and predictably—people flocked to restaurants in droves, and new case numbers have since gone way back up. It suited me for the time being though, as I hadn’t had a sit down meal for months (it was takeaway only when I was in Bulgaria, too; see here).

Restaurants in Istanbul opened for indoor dining the last two weeks I was in the city, so I braved the virus and enjoyed a few outstanding meals. Istanbul (and Turkey) excels in small, family-run little eateries where the food is fresh and well prepared.

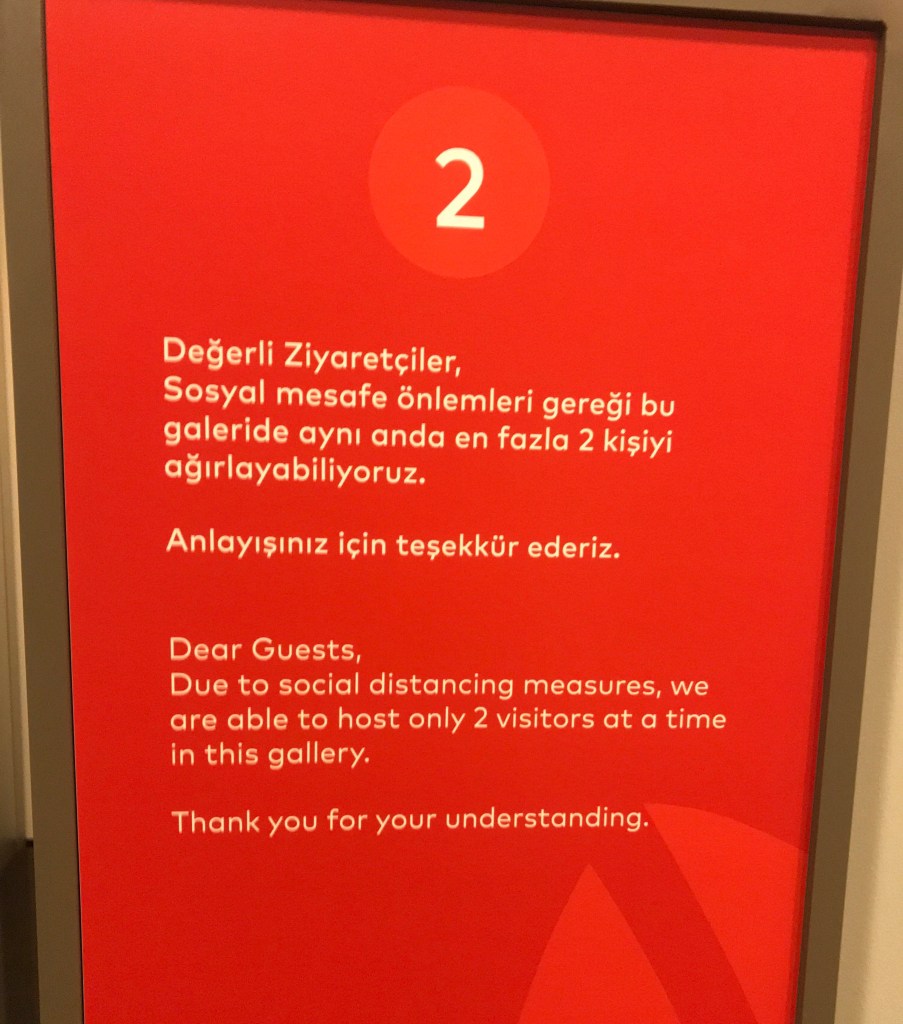

Like the rest of the country, everyone in Istanbul had to wear masks at all times in public, inside and out, even when walking down an empty street or in a park. There was a curfew in place every weeknight and all weekend from Friday night to early Monday morning. All residents were ordered to stay home, though trips to the grocery store, market, pharmacy and bakery were allowed. I carried on more or less the same way I’d been doing since I arrived in the Balkans back in October: I assumed Covid was bad, I wore my mask and washed my hands and stayed away from crowds or stuffy indoor places, and just went about my business. It was a terrific relief, actually, not to be bombarded with daily case count data, hospitalization numbers and future modeling predictions. I survived.

Rules we’re all familiar with now, no matter what the language.

I had to show a negative test result for Covid to get on my plane back to Canada, a second one after arriving at the airport in Vancouver, and yet another one on day ten of my self quarantine here at home. All tests came back negative, so whatever I did in Istanbul was enough to keep Covid at bay. To be honest, Covid was more of an inconvenience than anything else, and the main downside was not being able to sit down and eat in the wonderful family-run Turkish restaurants and tea houses, and not being able to go to the Turkish hamam (the bath). I’ll eat, drink, and bathe twice as much next time.

And when exactly might that be? Well, I just had my second vaccination shot on June 21, so…

Stay tuned!

* Remember! I love receiving comments, but anything you write, including when you hit “Reply” to the email notifications, is public. You know who you are…

* If you liked this story why not read some of my other blog posts? They’re all here. Photos are collected here.

Discover more from The Plain Road

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

FYI

On Fri, Jul 2, 2021 at 12:31 PM Andrew Wilson – Resting With Old Man wrote:

> arjwilson posted: ” Oh boy, where to begin… It’s difficult to write > about my experiences and impressions of Istanbul, because I find it hard to > know where to start. Like the city itself, staying focused on writing, and > not jumping all over the place, is a challenge. Ex” >

LikeLike

I loved this. Makes me want to get over to Istanbul as fast as possible and explore some of these neighbourhoods. Very well researched and beautifully illustrated. A really excellent read (as always !).

LikeLike